WDYK: The Legend of Jigger Johnson

Tales of a courageous, hard-working logger

In the late 1970s, I worked as a surveyor on a U.S. Forest Service crew in the White Mountain National Forest. Depending on where we planned to work the next morning, our team would determine the rendezvous location to meet at the night before. Jigger Johnson Campground on the Kancamagus was convenient when working in the Passaconaway area, so we regularly made plans to meet at “Jigger’s.”

While waiting for late crew members to arrive one morning, I asked a seasoned forest ranger, “Who was Jigger Johnson?” His answer sounded like a Paul Bunyan tall tale. Later, back in the office, the ranger retrieved an old folder and shared it with me. Inside were newspaper clippings, typed notes and book excerpts describing the life of Albert Lewis “Jigger” Johnson.

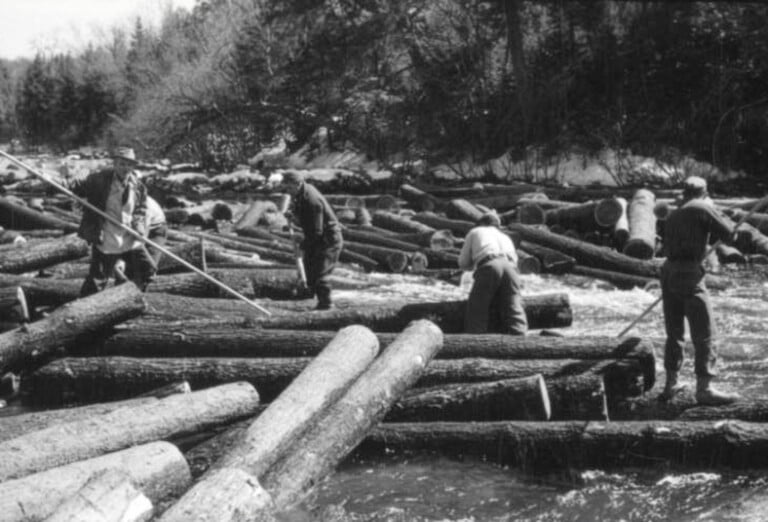

Jigger was a lumberjack, river log driver, trapper and fire warden for the U.S. Forest Service. The nickname “Jigger” seems to have originated with his small stature. While the tales about Jigger seem larger than life, his physical size wasn’t impressive. He stood

5 feet, 6 inches tall and weighed perhaps 150 pounds.

New Hampshire forester Bob Monahan is quoted in The Mountain Ear saying, “All of him was coiled steel-spring muscle, except his head, which contained brains-a-plenty. Those who witnessed him in battle still recall his courage and ferocious attack — no matter the odds against him.” Monahan says that Jigger worked hard, drank hard, fought hard and lived a hard life.

Jigger was born in 1871, in Fryeburg, Maine, and folklore says he came out of his mother’s womb with a wad of tobacco in his mouth, spiked boots on his feet, an ax in one hand and a peavy in the other. His childhood was brief. Jigger claimed he only attended two days of school in his life; the first day, he forgot his books and the second, the teacher was out sick. At the age of 12, Jigger went to work in a logging camp as a cook’s assistant.

He helped prepare food, served loggers, washed dishes and chopped firewood. In this camp, conversation was forbidden at dinner because it led to arguing, then fighting. This rule was challenged when new loggers arrived intoxicated. One of them insisted on talking loudly, and the scrawny young Jigger dutifully asked him to stop. The belligerent newcomer struck the boy and began pummeling him. Jigger bear-hugged the logger and sunk his teeth into an ear. When the two were pried apart, part of the big man’s ear remained in Jigger’s mouth.

The camp boss ordered the drunken loudmouth, with a missing chunk of ear, to start walking. Impressed with the grit of 12-year-old Jigger, he bought him a new shirt replacing the one torn in the fight.

Jigger worked his way up the logging camp ranks, and by the age of 20 was foreman of an outfit on the Androscoggin. The dynamics of managing these remote camps required that the foreman be able to out-brawl any of the men he supervised as well as out-drink, out-cuss and out-work them. As foreman, and one of the smallest and youngest men in camp, Jigger had to continually prove himself, and did not tolerate any backtalk from bigger antagonists challenging his authority. Relying on ferocity, strength and quickness, Jigger held his own in many brawls.

Jigger was an honest boss who paid his men fairly, but in return demanded a lot from them. On one occasion, Jigger told his men to wait in camp while he went to recruit additional log drivers. In his absence, some of the men snuck off to a local bar. When Jigger returned and discovered the men missing, he went after them. Jigger entered the bar swinging a peavy, and his logging crew quickly skedaddled back to camp without argument.

When the log drives came to an end in the early 1920s, Jigger hung up his spiked boots and retired as lumberjack. For a few years he worked as a fire warden in lookout towers on Mount Chocorua, Carter Dome and Bald Mountain. He also became an instructor at a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp where he taught young men about working in the woods. But the CCC life did not suit him. There were too many rules about shaving, bathing, drinking and mandatory study every night. Jigger left the CCC camps and took up fur trapping.

Monahan writes that as a trapper, Jigger was very successful and caught lynx, bobcat, mink, muskrat, weasel, beaver, fox and fisher. Bobcat and lynx became his specialty because of a bounty paid for them in addition to their pelt. But when Jigger discovered the wildcats were worth even more if captured alive, he learned to grab them barehanded and stuff them into a gunny sack.

One story tells of a windowless shack in a logging camp where the company stored dynamite. A wildcat had gotten inside and scattered blasting caps and dynamite all over the floor. No one dared go inside the unlit shed with a cornered wildcat. Jigger went in with a kerosene lantern and came out with the dynamite and a bagged wildcat.

Another tale tells how Jigger used a deer carcass to lure two bobcats beneath a tree he had climbed. When the bobcats took the bait, Jigger pounced from the tree and bagged them live, barehanded. He sold one of them to the University of New Hampshire for their wildcat mascot.

The end for Jigger Johnson came after selling a profitable lynx pelt and going into Conway to celebrate. The next morning, a hired man drove him back to Passaconaway to resume checking his traps. Their car slid off the road as Jigger was jumping out, pinning him to a tree. He was taken to a hospital and died of his injuries on March 30, 1935.

The old folder given to me by the seasoned ranger contains many more stories of Jigger’s colorful exploits. If even half of these tales are true, then Jigger Johnson, the river-driving woodsman, is worthy of this campground named in his honor … and I’m glad I asked who he was.