The Many Lives of the Wentworth By The Sea

Uncover the many lives of one of New Hampshire's grand hotels, which stands tall in New Castle, as many other hotels of its era have crumbled in disrepair

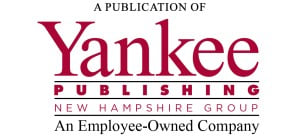

A 19th-century lithograph of summer life at Wentworth Hotel in New Castle, NH, during the Frank Jones era. Engraving Courtesy/ Portsmouth Athenaeum

Wentworth by the Sea is a survivor. It stands while so many other great Atlantic hotels of its era have disappeared. It did not burn, like most rambling wooden structures. In fact, it grew, expanding until the buildings dominated a quarter of the island town of New Castle.

It evolved and made international headlines. It went dark for two decades, then reappeared, phoenix-like. Today’s Wentworth is not a reconstruction. Only the front portico and its three towers date to the 1870s. The 21st-century Wentworth, instead, is reborn — a modern hotel with a historic heart.

Campbell & Chase

The location was too perfect to ignore. Someone, New Castle residents predicted, was going to build a grand hotel atop the scenic bluff on the southwest side of the island. That person, all but lost to history, was Mr. Daniel E. Chase. A liquor distiller by trade, Chase bought the land in 1873 from Sarah Campbell for $4,000, worth $100,000 today.

Described as “a manly man … in the Puritan character,” Chase had the funds, but Sarah and her husband, Charles, both New Castle locals, had the dream. Skilled in the hospitality trade, by June 1874, the Campbells found themselves managers of a boxy wooden hotel with 82 apartments known simply as The Wentworth.

The L-shaped structure offered magnificent views at every point of the compass: from Little Harbor, site of the first New Hampshire settlement in 1623, to the Isles of Shoals, coastal Maine, and the mansion of royal Gov. Benning Wentworth at the Back Channel, dotted with tiny islands.

An early newspaper account detailed an extensive entry hall and parlor with a grand piano, a reading room and a dining room

capable of seating 400 guests. A 14-foot-wide piazza wrapped the exterior on three sides. A gushing spring provided water. Gas lamps lit every room. The fine carpets and walnut and oak fixtures led up a wide stairway to an observation cupola on the roof with views of the White Mountains on a clear day. “The scene at sunrise and sunset,” a contemporary reported, “is as wonderful as fairy land.”

The primary activity at Victorian hotels was relaxing away from the heat and smog of industrial cities. Guests sat on the piazza in rocking chairs and watched the sailing ships gliding between harbor and sea. They lounged on the rocks and read, played cards and chatted. Eating was their second-favorite activity.

Physical fitness had not yet come into fashion, but for the vigorous souls, the Wentworth offered swimming in the protected bay, horseback riding, fishing and sailing. Carriages and ferries were available for those who wanted to view historic sites, attend church or shop in Portsmouth.

Following a banner first season, Daniel Chase threw money into buying more seaside real estate. In 1875, he added a new hotel wing. But Chase, according to New Castle historian John Albee, “forgot to count cost.” Shifting employees, skilled pastry chefs, a new billiard room, pier, bowling alley and stables all hit the bottom line hard. Then, amid a looming recession, Daniel Chase went bankrupt, abandoning Sarah Campbell and 92 other creditors. By 1877, the liquor distiller was out and the ale tycoon was in.

Enter Frank Jones

Business tycoon and former U.S. Congressman Frank Jones purchased The Wentworth in the late 1870s. Over 25 years, his investments changed the shape and size of the hotel, transforming it into one of the most exclusive resorts on the Atlantic coast. Courtesy/ Portsmouth Athenaeum

Where Daniel Chase saw a modest hotel on a hill, Frank Jones saw the grandest world-class luxury hotel in New England. Jones didn’t have to ask the bank for help. He owned the bank. He would come to own an insurance company, the local utilities, a railroad line, a brewery, horse racing stables, a theater and office buildings.

Born on a farm in Barrington in 1832, Jones was 16 when he delivered an oxcart full of charcoal to Portsmouth. From rag-picker to stove salesman to brewer, he showed uncanny business skill. A Portsmouth mayor and NH congressman, Jones left politics in 1879, the same year he purchased the Wentworth. He poured money into his new property, installing another story to the main building. He added three distinctive towers, each topped with the curved “mansard” roof that we recognize today. Extensive renovations doubled the length of the hotel to 160 feet.

Manager F.W. Hilton took wealthy guests up a steam-powered elevator to 200 beautifully appointed rooms. A 20-piece Boston orchestra was in residence for the entire summer. Hilton instituted athletic competitions, a longtime Wentworth tradition, featuring sprints, tennis, golf, baseball, rowing and swimming events. Wentworth horses were immaculately groomed. Carriage drivers were prompt and neatly dressed. Hundreds of anonymous workers were seen, but not heard. A marketing genius, Hilton broadcast news of the luxurious accommodations throughout the East. Patrons from Louisville, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis dominated the hotel register.

“These are men of wealth and refinement,” manager Hilton told the press. “They want the best service, and are willing to pay for it … Their entire families appreciate the atmosphere at the Wentworth, and leave it with regret.”

Tapping his congressional contacts, “The Honorable” Frank Jones arranged a visit by President Chester A. Arthur. In September

1882, the president and his entourage breakfasted at the Wentworth. They praised the view from the roof before stopping by Jones’ Rockingham Hotel in downtown Portsmouth, now converted to private apartments. Even a whistle-stop visit was enough to affix the presidential seal onto the hotel advertising campaign. Jones openly offered to give the new president a free parcel of land if he wished to build a summer cottage in New Castle.

Of all its innovations, none was more welcome to the Victorian traveler than the marvelous water closet, although, at first, only a few were added to each floor. They flushed directly into Little Harbor, from which the mighty tides carried the effluent out to sea. Jones also pioneered the use of electricity. In July 1880, seven outdoor electrical arc bulbs cast a flickering, futuristic glow over New Castle for the first time. Jones built his own coal-fired plant that, initially, supplied power to his Portsmouth mansion and his two local hotels. By 1895, the outline of the hotel was lit by hundreds of bulbs. Observing the scene from across the Piscataqua River, a reporter wrote: “Its grandeur dwarfs all other hotels on the Maine and New Hampshire coasts until they become almost insignificant.”

Peace Treaty and beyond

Although President “Teddy” Roosevelt did not show up in person, he orchestrated the successful 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth and won the Nobel Prize. Delegates from Russia and Japan stayed in separate wings at the Wentworth. They took a short boat ride daily to negotiate in the “Peace Building” at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Maine. Photos Courtesy/ Portsmouth Athenaeum

Frank Jones never lived to see his greatest triumph, but he set the stage. Before he died in 1902, he nearly doubled the size of his

hotel. The Wentworth Annex was designed to function independently. It had its own parlor and office, a billiard area, rooms to sleep 100 guests and an innovative separate dining facility built onto the top floor. Half a world away, Japanese and Russian soldiers were locked in a territorial conflict that had killed half a million men. For Ports-mouth residents, until the summer of 1905, the Russo-Japanese War was no more than an emperor battling a czar in a distant and mysterious land.

Fearful that the balance of world power was shifting dangerously, President “Teddy” Roosevelt invited the two nations to meet on neutral ground. Roosevelt wrote: “I am taking steps to try to choose some cool, comfortable, and retired place for the meet-ing of the plenipotentiaries where conditions will be agreeable and where there will be as much freedom from interruption as possible.”

The Wentworth, now two conjoined hotels, was selected as the home base for both delegations. In August, 1905, Japanese and Russian envoys arrived to find a boisterous welcoming parade. For one month, the delegates shuttled back and forth by navy cutter from the Wentworth to the secure brick “Peace Building” just across the Piscataqua River at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery. A hundred journalists jostled for newsy tidbits. Photographers captured Sergei Witte of Russia and Jutaro Komura of Japan staying in separate wings of the hotel.

It was a nail-biter, but in the final hours, a treaty ending the bloody war was signed. The mayor of Portsmouth ordered church bells to be rung for a half-hour, a tradition honored annually in Portsmouth. “PEACE!” The newspaper announced in 5-inch letters on Aug. 29, 1905. Historians continue to debate what went right in the successful Treaty of Portsmouth.

Sold and sold again, the now-famous Wentworth adapted to the times. In 1916, as the First World War loomed, new owner Harry Priest hired the hotel’s most famous employee. Gray-haired, but as precise as ever, 58-year-old Annie Oakley demonstrated her riding and shooting skills on the hotel grounds.

Golf and swimming dominated the Harry Beckwith era that stretched from the Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression. His engineers created a deep, massive pool with a cement floor. Filled with seawater by the tides, it had to be pumped dry and scrubbed clean every three days. Beckwith also introduced “The Ship,” a massive wooden casino shaped like a cruise boat. Here, guests could view Olympic divers, listen to live music, attend movies and lectures, or watch boxing matches. One critic described The Ship as “an ocean liner stuck on a reef.”

But the guns of war were sounding again. Contrary to legend, the Wentworth was not painted black during World War II as a defense against marauding German submarines. Instead, the lights were simply switched off, the resort “blacked out,” and the doors shuttered.

Margaret and Jim

Harry Beckwith wouldn’t take a penny less than $200,000. It was way more than Margaret and James Barker Smith had in 1946, but they couldn’t resist the offer. The Wentworth sale included the sprawling 256-room hotel, its staff dormitories and outbuildings, The Ship and tidal pool, docks, and the golf and tennis courses, plus the Beckwith summer house and several hundred acres in Rye and New Castle. Born to the hospitality trade, the couple from Kansas and Colorado would run their summer resort for three decades.

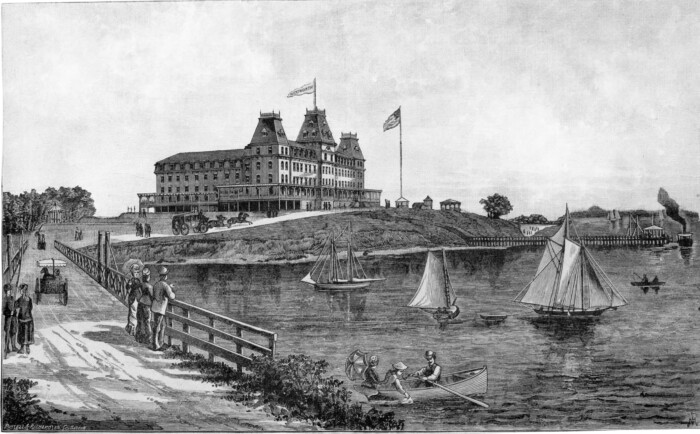

Margaret handled the business while Jim acted as genial host. Each week followed a strict schedule of cocktail parties, movies, ballroom and square dancing, masquerades and concerts. Post-war Americans rushed to rusticate amid the fading grandeur of a bygone era. The Smiths, like their forebears, initially ran an “exclusive” hotel that shunned Jewish, Catholic and guests of color. But by the mid-1960s, those barriers were shattered by law, by economics and by shifting social norms.

Margaret and James Barket Smith, skilled hoteliers, purchased the exclusive hotel in 1946 and managed Wentworth by the Sea for 34 summers. Courtesy/ Portsmouth Athenaeum

Despite rumors to the contrary, celebrity guests were few and far between during the Smith era. Actress Gloria Swanson was clearly on the scene. Also sighted were actors Jason Robards, Fred Rogers and Zero Mostel, columnist Ann Landers, athlete Arnold Palmer, and economists Milton Eisenhower and John Kenneth Galbraith. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover went unseen, but his thank-you note is in the Smith Collection archive. Vice presidents Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon and Dan Quayle shared the podium with presidential hopefuls Ralph Nader and Sen. Edward “Ted” Kennedy. Archived photos show the Smiths posing with Prince Charles in 1973.

The couple thrived by inching up room rates while extending the summer opening and fall dates. They kept employee wages low and hosted as many as 250 conventions and business gatherings annually. The Smiths, who wintered as managers of a hotel in Florida, ran a tight ship. But maintaining the aging property, Jim Smith claimed, swallowed a quarter million dollars annually. In the fall of 1980, after 34 summers by the sea, James and Margaret Smith called it quits. Their reign over the magic kingdom was complete, and their departure, though regal and well deserved, nearly brought the castle down.

Phoenix rising

With the Smiths gone, the hotel itself appeared to lose heart. After a failed revival by their son James Smith Jr., Wentworth by the Sea closed for the next 22 years. Half a dozen owners followed, but each seemed more interested in the great expanse of scenic Wentworth property than in the waning hotel itself. None of the owners were truly “hotel people,” and with each sale, the building and its surrounding estate grew smaller.

A 19th-century brochure illustration shows a near-identical image with hundreds of hotel guests seated in the massive dining room that, as shown by this 20th-century photo, survived into the Smith era. Photo Courtesy/ Wentworth by the Sea

By the 1990s, surrounded by a metal fence, only a battered portion of the original building was left standing on 4 acres. When former Wentworth tennis pro Wadleigh Woods, then in his 90s, visited the ruined site, he wept. But there was a faint pulse. What began as a local effort to slap on a fresh coat of paint became the nonprofit Friends of the Wentworth. Led by Etoile Holzaepfel, a New Castle landscape architect, the group lobbied tirelessly to find an owner. “We are not interested in preserving it as a relic or as a museum,” Holzaepfel told reporters. Use it or lose it was the group’s motto.

Years of negotiations passed. Then, on Feb. 19, 1997, a Portsmouth Herald banner headline proclaimed: “The Wentworth is Saved.” Ocean Properties, a locally owned hotel management company, agreed, conditionally, to buy and rebuild “the grand dame of the Gilded Age.” It would take six more years and $26 million. Today, because the building stands, its countless stories, preserved within the original beams, are being told and told again.

In the Happiness Business

Mary Carey Foley is on a mission. Her official title at Wentworth by the Sea is concierge. Her real job, she says, is “to make people happy.”

“I just think of my mother,” Foley says. “She made the best out of everything. I try to be like her every single day.”

Her mother, Eileen Foley, was the longest-serving mayor in Portsmouth history. Mary’s grandmother, Mary Carey Dondero, was elected the city’s first female mayor in 1945. Those are big shoes to fill.

“When my brothers, Jay and Barry, and I were growing up in the 1950s, for a treat after Friday dinner, our family would take a ride around the New Castle loop,” she recalls. “We’d stop for ice cream at Bartlett’s (later the Ice House). A cone was 5 cents with sprinkles! Passing the hotel always fascinated me. My parents were married at the Wentworth. It was just so beautiful. The older I got, the more I wanted to work there.” More than half a century later, Foley got the job.

“Now I’m always at work,” she says. “I’ve been here 19 years. I’m the concierge, but I also do Thanksgiving dinner and the Christmas buffet. I do the wine festival. When it’s not too busy, I’m around back answering the telephone.” As a justice of the peace, Foley notes, she is even available to officiate at weddings.

“The Wentworth is as special as the first day I started work,” she says. “I’m turning 75, but I’m like one of the kids here. I’ve gotten very close to a lot of my guests over the years. They’re not just customers. They’ve become my very, very close friends.”

J. Dennis Robinson is the author of 20 history books for readers of all ages, including Wentworth by the Sea: The Life & Times of a Grand Hotel. For more information visit jdennisrobinson.com.