The Last Sound Ranger

J. Dennis Robinson tells the story of John B. Robinson, his 102-year-old father, and his role at the Battle of Iwo Jima

Earlier this year, my father, John Brewster Robinson, finally spoke publicly about his secret World War II mission. As kids, my two brothers and I knew he had been a U.S. Marine. We knew he fought in the Battle of Iwo Jima, the one where six men raised that iconic flag, a symbol of American valor and resolve known around the globe.

A 3-cent U.S. stamp issued on July 11, 1945 honoring the U.S. Marines at the Battle of Iwo Jima. Photos: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Dad never talked about the 6,821 men who were killed during the 36-day battle. Another 19,217 fellow soldiers were wounded in the deadliest encounter in Marine Corps history.

On Nov. 10, 2025, the Marine Corps celebrates its 250th birthday. My father is 102. He delivered this historic speech, coincidentally, on his birthday on April 30. Approximately 100 people, many of them veterans, gathered at the Senior Activity Center in Portsmouth for the talk. Formerly of Bedford, he’s been living at The Inn at Edgewood, an assisted-living facility just up the road.

Dad brought a few scribbled notes, but never used them. His right leg, he complained, had a mind of its own, so he remained seated as he spoke. He spoke purposefully, like a man getting something off his chest. I was so busy showing a few slides to accompany his talk that I neglected to record the lecture. A TV station taped it, but erased the file the next day.

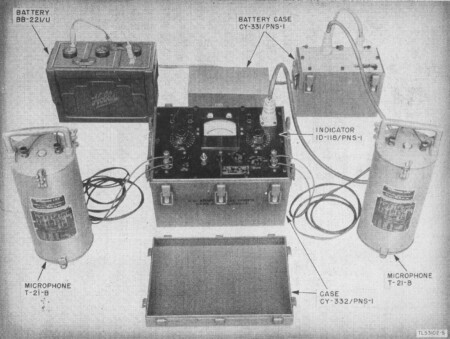

So, Dad and I sat down recently to reconstruct his story. His memory remains crisp. Eighty years ago, 21-year-old Staff Sgt. John Brewster Robinson and a handful of trained “sound rangers” landed on the volcanic island of Iwo Jima amid ferocious enemy fire. They were the DODAR Team (Detection of Distance and Range). Their mission was to pinpoint hidden Japanese artillery using microphones, wires, vacuum tubes, dials, batteries and test equipment. With the microphones strategically placed and the equipment tuned to the frequency of the deadly booming guns, the team could triangulate the exact position of the hidden cannons and radio the data to American gunners. At least, that was the theory. So how did a skinny kid from New England wind up in one of the worst places on Earth?

Left: John B. Robinson in training with the DODAR Sound Rangers in World War II.

Right: The DODAR Sound Ranging Team in the USA prior to intense training on the Big Island in Hawaii.

From hat factory to boot camp

John Robinson was born in Milford, Mass., in 1923. His mother, a teacher named Florence, was forced to quit work when her pregnancy began to show. Unhappy with life on the Robinson family cattle farm in Hardwick, Mass., John’s father, Jason, became a fur trapper, a florist and a night watchman. When we knew Grandpa Jake decades later, he was making custom cherry cabinets, sharpening saws, selling vegetables and raising giant worms in bathtubs under the barn in the town of Orange. John was so sickly that, at age 4, his mother and father sent him to live with his grandparents in a little Massachusetts town called Upton. They never asked him back.

Reclusive and bookish, John was a master builder of model airplanes by age 8. The Upton town “telephone man,” he recalls, made annual home visits to replace worn batteries. John got his hands on the used batteries to power his motorized inventions. In a high school class of 25, he excelled at math and was on the track to attend college as war in Europe loomed.

To help support his aging grandparents, John worked after school at the Knowlton Hat Factory in Upton. The only decent paying job in town was not without danger. Mercury and sulfuric acid were key to the manufacturing of fashionable felt hats, leading to the term “mad as a hatter.” John remembers boys darting in and out of the 200-degree drying room. “We figured we were safe if we held our breath,” he says.

“We assumed we would be drafted,” he recalls of the Upton Class of 1941. Those who survived military service, the boys figured, would return to work at the hat factory. He joined the Massachusetts National Guard, but it “was not much of anything but learning to march and puttering around for two hours a week.”

U.S. forces landing vehicles on Iwo Jima beach in February 1945. It would become the deadliest battle in Marine Corps history. Photo Courtesy/ US Naval Community College (USNCC)

Horror struck the nation on Dec. 7, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Air Force bombed the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The next morning, John and three teenage friends drove to Boston in a borrowed car. One enlisted in the Navy, one in the Air Force, and a third in the Army. John selected the Marine Corps in hopes of being trained as a telephone electrician. He was accepted and arrived at Parris Island Boot Camp in South Carolina on Christmas Eve.

Thirty boys, mostly teens, found themselves in a spare barracks with a tough commanding officer. (“We never walked. We always ran.”) John got the top bunk above a young black soldier. “I was socially inept, and he was the nicest guy you ever saw in your life.” The two were fast friends for the next seven weeks and never saw one another again. By the end of boot camp, Pvt. Robinson had put on 30 pounds of muscle.

Beach Jumper to Sound Ranger

At first, Field Telephone School was “very basic,” he recalls. “We were shown the telephone and told that it worked — but not to ask how.” Recruits did little but change batteries. Then, after a cluster of special tests, mostly in math, John was whisked off to Anacostia Naval Base in Washington, D.C., where he was the lone Marine among 127 Navy men. The eight-month course in electrical interior communication (EIC) was intense, but there was time off to attend church, visit museums, see movies and meet people.

Transferred to Norfolk, Virginia, he was assigned duty as a “Beach Jumper” with no clue as to what that was. The Beach Jumpers was a secret operation originated by actor and Lt. Douglas E. Fairbanks Jr. The group of highly trained electrical experts planned to use experimental equipment to distract the enemy from spotting U.S. troops landing on foreign soil. “We were told it was not exactly a suicide mission,” John says.

First, they recorded the live sounds of American tanks, trucks and troops onto wire recorders. Those recordings would then be played for the enemy on powerful hidden speakers. Sounds of the mock landing would buy time for real American troops to land. The 1940s technology, however, did not live up to the concept. During a test, with military brass watching, the fragile wire recording snapped, and the project was scrapped.

Reassigned to the base at Quantico, Virginia, John joined a newly formed “Sound Ranging Squad.” While fighting in the Pacific, U.S. Marines were being harassed and killed by hidden Japanese guns that could fire without being detected. The physics department at Duke University was developing a defensive device, nicknamed DODAR. The equipment was portable and sturdy enough to be used in the field to locate the invisible artillery. Japanese gunners, it was later discovered, could swing their cannons out on tracks, fire and vanish into camouflaged tunnels before the shells landed.

Into the jaws of hell

The 5th Marine Division, known as the “Fighting Fifth,” was created to spearhead the invasion of Japan. The heavily defended island of Iwo Jima stood in the way.

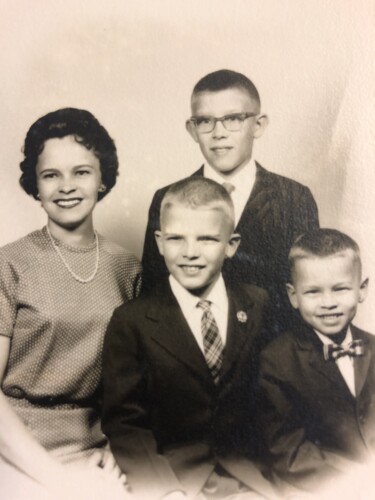

Phyllis Scott Robinson in the 1960s with sons, from left, Brian Scott, John Dennis, and Jeffrey Alan Robinson. Photo Courtesy/ Robinson Family

“That mission was the whole thing. There was nothing else,” John says.

He found himself on a train to San Francisco, then aboard a cargo ship to the Big Island in Hawaii. The sound rangers spent the next year isolated 40 miles from the nearest city, training seven days a week.

The student was now the teacher. Soldiers set up dynamite charges along 20 miles of isolated lava beds. The DODAR Team, under John’s direction, was tasked with triangulating the exact location of each test explosion. Unlike the Beach Jumpers, the sound-ranging equipment created at Duke University offered promise. “Everything worked exactly as planned,” John says. But the boy from New England didn’t love life in paradise.

“Every day was exactly the same,” he jokes. “It was warm. There was no wind. It sprinkled a little. It was boring. I went swimming on Christmas, and it was 72 degrees. I went swimming on the Fourth of July, and it was 72 degrees.”

He tried surfing, but didn’t have the balance. Then suddenly, the Fighting Fifth was back aboard ship for a week, cruising at 8 knots. “They didn’t tell us where we were going until we were halfway there,” he says.

The Sound Ranging Unit arrived at Iwo Jima in the early afternoon of Feb. 19, 1945, a date John still calls “my D-Day.”

“We kept our heads down and heard shells hitting close by in the water,” he says. Landing vehicles got stuck in the volcanic ash, leaving them vulnerable until track vehicles could pull the duck boats onto solid ground. Getting the sensitive sound equipment ashore and into foxholes was hair-raising. John’s boss, Cmdr. William N. Martin, had done his homework. Using aerial photographs and written instructions, the sound rangers knew exactly where to work.

“We were equipped to protect ourselves, but we never took our rifles off our backs. We weren’t there to battle anyone. We were there to run an experiment.”

John B. Robinson is welcomed into his new home at the Edgewood Inn in Portsmouth by owner Patricia Ramsey. Photo by J. Dennis Robinson

The microphones were hastily set into holes at precise locations. But digging in the lava beds was nearly impossible. The volcanic earth kept crumbling back into the hole. The solution was to place a spent artillery shell in the hole with the microphone inside. With the mics set 200 feet apart, the wires connected to the generator and DODAR unit, the testing began. The team slept on the ground without tents or blankets. There was no wash water and only a single change of clothing for the month-long operation.

Four days in, just after the raising of the famous flag, the DODAR time began getting a bead on the destructive enemy gun. The coordinates were transmitted. The Marine artillery returned fire moments later, and the Japanese cannon fell silent. The danger was far from over, but John Robinson’s war narrative stopped there.

“I avoided talking about it in every way I could for the next 50 years,” he says.

Then in the 1990s, his middle son, the late Brian Scott Robinson, began digging for details. The metaphor is apt. A prominent archaeologist, Brian began excavating the facts from his father’s memory. The result was a richly detailed and still unpublished 40-page report titled “It Could Only Be Found with Sound.” Rereading that report is what inspired John to go public with his largely forgotten mission during a lecture on his 102nd birthday.

On to Japan

Two days after the battle, heading back to Hawaii, John was discovered curled “in a birth position” in his bunk. An emergency appendectomy aboard ship followed. Coming out of the anesthesia, Sgt. Robinson was given a new assignment. “Don’t move a damn muscle for 24 hours,” the medic commanded. Back on the Big Island, after two weeks of bed rest, John and the DODAR team went back to their testing regimen.

With Iwo Jima secured, U.S. forces were within striking distance of mainland Japan. By the first of August, following ferocious fighting in the Battle of Okinawa, the Japanese military still refused to surrender. The 5th Marine Division, “the tip of the spear,” was among the forces headed to Japan as part of the Allied invasion nicknamed Project Downfall. John and the DODAR team were aboard. The U.S. government feared massive casualties.

“We were probably five days into the trip to Japan when word got out that America had bombed Hiroshima,” John says. “I wouldn’t be here now if they hadn’t. The war was over.”

Instead of searching for hidden artillery, the sound rangers were assigned to enforce the terms of the Japanese surrender. John and his group occupied an enemy warehouse, “demobilizing” enemy supplies and providing essential services to a deeply traumatized population. “They had given up,” he says of the locals, “and they were lost.”

His key liaison was the son of a local government official. “He was a kid about my age. He was the interpreter for the town because he had studied English in high school. He could write it, but had no idea how to pronounce the words. We spent our days together. At the end of the day, he would go back home, and I would go back to the warehouse to play cribbage. Each morning, he would return and ask: ‘Is this the day you kill me?’”

For three months, the sound rangers played cards and ate “very tasty” rations. Their warehouse was almost blown away by a typhoon. Suddenly, they were on a troop ship with hundreds of soldiers on a long journey home. Discharged in South Carolina, John traveled by train to Massachusetts with only a uniform and a knapsack. He stepped off the bus in Upton to learn that his grandfather, the man who raised him, had died the previous day. John arrived just in time for the funeral.

Despite an “essential tremor,” John Robinson continued to build models to age 101. Last year, he finished this wooden kit of a Lowell Grand Banks Dory. Photo by J. Dennis Robinson

“Anything we owned had been shipped ahead in a cardboard trunk,” he adds. “We were all required to take a Japanese rifle. As soon as I got settled, the first thing I did was give it to my father, who put it up over his mantel. The whole military thing was over for me.” Each discharged soldier was given $300 cash. John spent his entire windfall on a collection of classical music on 78 rpm records.

The hat factory wanted him back, “but I wanted nothing to do with it,” he says. John worked with an aunt and uncle who lived just up the road. He soon met and wed Phyllis Elizabeth Scott. They were married for 70 years. Based on his training, John got a job with New England Telephone and Telegraph, later AT&T. He was a telephone man for life.

In 1960, with sons Dennis, Brian, and Jeffrey, the Robinsons moved to Bedford, NH, and settled into a little ranch house. When not working for Ma Bell, John built model airplanes, fiddled with electronic devices, and listened to classical music. He fixed every TV set in the neighborhood for free. He never drank alcohol, smoked cigarettes or swore. He never missed a day of work in 35 years. He retired early. And until his 102nd birthday, on Aug. 30, 2025, he went out of his way to avoid talking about the war.