Stealing the King’s Powder: Did The American Revolution Start Here?

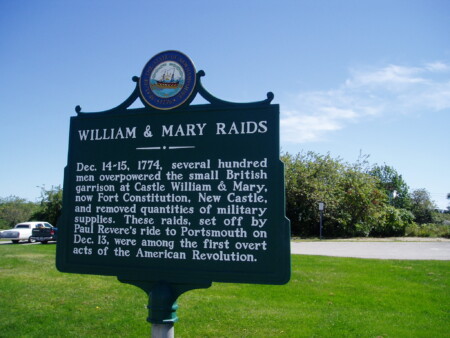

Local historians have long proclaimed, not always tongue-in-cheek, that the American Revolution began in New Castle, New Hampshire, rather than on the bloody battlefields of Lexington and Concord.

The 1774 winter raid on Fort William and Mary, when hundreds of seacoast residents robbed the king’s armory of a hundred barrels of gunpowder, was an outrageous act of colonial defiance. Its leaders, John Langdon and John Sullivan, were committing treason and risking the gallows.

A 19th-century issue of “Harper’s Weekly” called the raid on Fort William and Mary the “most dramatic” and the “most important” event leading up to the American Revolution. It was “unquestionably the first act of overt treason” in the war, yet barely one in 100,000 Americans “could recall any of the circumstances of that noteworthy event,” the magazine claimed.

Today, the uprising rarely rates more than a footnote in most histories of the War for Independence, and now, the “Portsmouth Alarm” teaches us how decades of simmering colonial frustration finally boiled over into a full-on war with Mother England.

Loyal but discontented

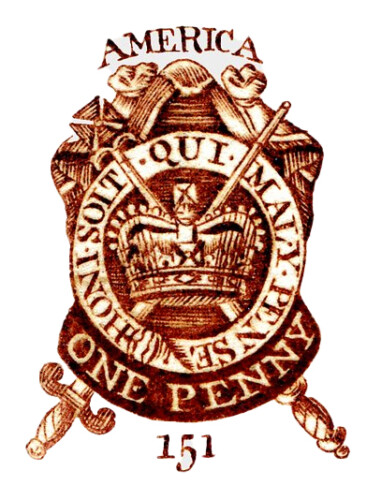

We know from the first 150 years of New Hampshire history that residents were a cantankerous lot. Having irritated Massachusetts Bay Puritans and rankled royal governors for generations, they were unlikely to sit still for the latest wave of British taxes. Portsmouth residents and the newly formed “Sons of Liberty” reacted violently to the Stamp Act of 1765 that slapped a royal tax on legal documents and printed publications. A mob hanged and set fire to an effigy of Portsmouth-born stamp tax collector George Meserve and drove him from town.

Wealthy leaders, many with enslaved servants, often argued that British taxes were tantamount to placing Americans in bondage. It wasn’t, but the metaphor was widely used. For all their protests, American colonists were paying barely 5% of the taxes levied on British citizens living in England.

Sons of Liberty, an often-thuggish group of early “patriots,” harassed custom officials and those store owners who sold imported British items. And yet by 1770, most Americans, including residents of New Hampshire, remained loyal to the Crown.

The year 1774 dawned only 16 days after the Boston Tea Party.

But contrary to what most of us learned in school, colonists from New Hampshire to Georgia were horrified by what they saw, not as patriotism, but as “anarchy” and “mob rule.” The Boston rebels had gone too far, many Americans believed, by dumping 92,000 pounds of tea into Boston Harbor. Even Benjamin Franklin called it “an act of violent injustice.”

Parliament struck back by sending troops to close the port of Boston. Prime Minister Lord North announced: “The Americans have tarred and feathered your subjects, plundered your merchants, burnt your ships, denied all obedience to your laws and authority…Whatever may be the consequences, we must risk something; if we do not, all is over.”

Royal governors like John Wentworth, born in Portsmouth, were caught in the crossfire. Despite building a beautiful new lighthouse at Fort Point, launching Dartmouth College and constructing highways deep into the New Hampshire wilderness, Wentworth’s power was fading.

It was in 1774 that the term “Loyalist” first appeared. These were American citizens who openly supported King George III of England. Disloyal subjects, later to be called “patriots,” were growing bolder day by day. “Everything is unhinged,” one Loyalist exclaimed, “and running into confusion.”

King George, angered by his disloyal subjects, issued an “order in council,” similar to an executive order by an American president today. It would spark the Portsmouth Alarm. The order banned the exportation of gunpowder and military arms to the rowdy Americans. It also required British troops to secure all munitions already stored in New England. The powder and guns at Fort William and Mary in New Castle were especially vulnerable to attack. Ignored for decades, the ancient fort was in ruinous condition and guarded by only six men.

Enter Paul Revere

Word that British soldiers aboard HMS Somerset were not far off the coast of New England reached the Boston Committee of Commerce on Dec. 12. Assuming the troops were headed to Portsmouth, activist and silversmith Paul Revere, a member of a secret group known as the Mechanics, left early the following morning on horseback. His mission was to warn Piscataqua locals that the British were coming.

The Somerset, however, was not headed to Portsmouth, but struggling far off at sea amid a frigid early winter storm. Revere slogged 60 miles through deep snow toward Portsmouth along the frozen wagon-rutted Old Bay Road.

Aerial view of the historic fort at the mouth of the Piscataqua River. Passing nearby is a replica gundalow. Ralph Morang/The Gundalow Company

Revere made his largely forgotten Portsmouth journey on Dec. 13, exactly one year after the Boston Tea Party. He arrived in Market Square at 4 p.m. with the snow still falling. Revere asked a passerby for

the whereabouts of Samuel Cutts, a leader of Portsmouth’s Committee of Correspondence.

Cutts, a prominent merchant with a powdered wig, a slight paunch and a bit of a double chin, happened to be walking downtown. He met briefly with Revere at Stoodley’s Tavern on Daniel Street. Today that historic building is part of Strawbery Banke Museum.

By noon the next morning, fired by the sounds of fife and drum, as many as 400 residents were prepared to storm the fort. John Langdon, a 33-year-old sea captain turned shipowner and merchant, was among the leaders of the protest. The soft-spoken rebel would later become one of New Hampshire’s first governors.

Striking the British flag

Led by Langdon and Thomas Pickering, the defiant mob grew. Hundreds clambered into small boats and onto flat-bottomed barges called “gundalows” for the journey downriver to the fort. Capt. John Cochran ordered his tiny troop to position the fort cannon for an attack. Any man showing a hint of cowardice would receive “a brace of balls through his body.”

Cochran allowed Langdon and one companion to come inside the gates for a brief discussion. Langdon informed Cochran that they planned to carry away all the munitions. If they tried, Cochran told Langdon, “Their blood be upon their own hands for I will fire on you.”

And he did. The besieged guards hurriedly fired 4-pound iron balls from three cannons, injuring no one. Musket balls zinged into the ground in front of the rebels. Bullets struck a warehouse, pierced the sail of a nearby ship, and even reached a Kittery home on the Maine side of the Piscataqua River. Before the guards could reload, the attackers stormed over the walls of the dilapidated fort on all sides.

It was British citizen versus British citizen, neighbor against neighbor, in what local historians call the first real battle of the American Revolution. Castle guards brandished bayonets in an impossible hand-to-hand struggle. They were disarmed, punched and threatened. One raider was stabbed in the arm. Capt. Cochran was jumped, choked and disarmed.

When he refused to turn over the keys to the powder house, raiders dragged him to his home within the fort walls, where Cochran’s wife, Sarah, briefly held off her captors with a bayonet. The raiders smashed their way into the armory with axes and crowbars to reach the precious powder.

A detailed account of the Fort William and Mary raid comes from Thomas F. Kehr, a modern Concord, NH, attorney who has been known to reenact the role of John Langdon in costume. “To Cochran’s undoubted horror,” Kerr writes, “the rebels triumphantly ‘gave three huzzahs or cheers’ and hauled down the huge British flag that had — for more than a century — declared British possession of Portsmouth Harbor.”

In defiance of law

225th anniversary re-enactment of raid on Fort William and Mary (Fort Constitution), New Castle, NH, by the Newmarket (NH) Militia

The following morning, Dec. 15, was bitterly cold and raining. The raiders had taken all the gunpowder save one barrel, Cochran reported to Gov. Wentworth. Barrels weighing about 100 pounds each were already being shipped by gundalow to hiding places in seacoast towns. Exeter reportedly received 72 casks.

After hiding some of the stolen powder in Durham, John Sullivan traveled 10 miles back to Portsmouth where he met with Wentworth. The governor told Sullivan, truthfully, that the treasonous raid was based on a false alarm. Paul Revere was wrong. No British troops had been assigned to New Castle. The rebels, Wentworth warned, must return the stolen powder.

The debate over what to do next raged on in taverns, in homes and in the now-dark and cold streets of Portsmouth. By 10 p.m., Sullivan and a hundred men were back at the gates of the fort. Despite promises not to steal any more of the king’s weapons, Sullivan’s men did exactly that, loading 16 small cannons, 10 cannon carriages and 42 muskets onto gundalows. The work took all night and the raiders had to leave the larger cannons behind.

Escape was a slow-motion nail-biter on Dec. 16, with their gundalows stranded by the shifting Piscataqua tide. As Sullivan’s men inched their way inland on the ice-choked waters of Great Bay, two British warships finally sailed from Boston toward New Castle. HMS Canceaux, a British merchant sloop converted into a 16-gun warship, arrived within sight of the fort by the following evening, but the raiders had disappeared.

The nonprofit gundalow “Piscataqua” offers Seacoast visitors the chance to experience life aboard a historic “river workhorse.”

The die is cast

How deeply the little New Hampshire raid influenced mighty King George III will forever be debated. For George, who saw himself as the parent to his millions of colonial children, it was all about respect, fealty and compliance. The Americans, as he famously told Lord North, “would either submit or triumph.”

In February 1775, King George signed off on Lord North’s latest punitive laws. “His heart was hardened,” a contemporary wrote of the monarch, “having just heard of the seizure of ammunition in New Hampshire.” King George decided it was finally time to “open the eyes of the deluded Americans.”

Massachusetts, British leaders claimed, was officially in a state of rebellion. General Gage, stationed in Boston, received orders to quash the American insurrection, by force if necessary. On April 19, 1775, the “shot heard round the world” was fired by an unknown hand, either redcoat or minuteman, and the American Revolution officially began.

Follow the powder

Did any of the king’s stolen gunpowder reach the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775? Seacoast chronicles often make this claim. A sign at a small, restored brick powder house in Exeter says so, as does a state historic marker in New Castle. According to local legend, a few kegs were kept under the pulpit of the Durham meetinghouse,

not far from John Sullivan’s home on the Oyster River.

Eventually, the powder was dispersed and hidden from Tory eyes at inland towns including Nottingham, Epping, Brentwood, Londonderry and Kingston. It was squirreled away in homes, taverns, barns and churches. Four barrels found their way to the tavern of Zaccheus Clough in Fremont (formerly Poplin). Four more were reportedly stashed somewhere in Portsmouth.

The nonprofit Friends of Fort Constitution hopes to revive the ruined historic New Castle site now considered unsafe by the NH State Parks Department.

A few barrels, history tells us, were assigned to John DeMerritt, Jr., who buried them behind a false wall in his cellar in Madbury, or in his barn. “Powder Major” DeMerritt, as he became known, delivered his supply to Boston slowly by oxcart in time, we are told, for the final hours of the deadly Bunker Hill encounter.

It’s a little-known fact that the fighting New Hampshire men at Bunker Hill, estimated at between 1,000 and 1,300, outnumbered the forces from Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. John Stark, James Reed, Enoch Poor and Henry Dearborn are among the Granite State militia leaders best remembered today.

Exit John Wentworth

Sir John Wentworth had a lot to lose if war broke out. He had recently built a spacious home in a wilderness that would become the town of Wolfeboro. His massive mansion sat on 4,000 acres with extensive gardens, orchards and vineyards near what is now Lake Wentworth. But he was forced to leave it all behind.

Months after the Powder Alarm, a Portsmouth mob pointed a cannon at the governor’s front door and threatened to blow it open. With the life of his wife Frances and their 5-month-old son in jeopardy, the royal family fled. During a scuffle, according to Portsmouth lore, guns were fired. A series of what may be bullet holes can still be seen in the wallpaper plaster above the mantelpiece in what is now an office of the Wentworth Senior Living facility on Pleasant Street.

The governor’s last New Hampshire residence, ironically, was at the tumble-down walls of Fort William and Mary in New Castle. The Wentworths were forced to live with the Cochran family. Their “small incommodious house” inside the walls of the fort had a leaky roof. “I will not complain,” Wentworth wrote to a friend, “because it would be a poignant censure on a people I love and forgive.”

But by mid-August, 1775, the governor of New Hampshire — a man with a master’s degree from Harvard College and a doctorate from Oxford University — was reduced to begging for food. The Wentworths and their entourage sailed to Boston aboard the British ship of war Scarborough on Aug. 23. Within half an hour after their departure, locals vandalized the undefended fort.

The New Hampshire General Assembly officially banned John Wentworth, under penalty of death, from ever setting foot in the province where he was born. Half a century later, as lieutenant governor of

Nova Scotia, he died in Halifax in 1820. He was 84.

Does the almost-forgotten raid matter today? According to Paul Revere biographer David Hackett Fischer, “These were truly the first blows of the American Revolution.”

J. Dennis Robinson is the author of over a dozen books including “1623: Pilgrims, Politics, Pipe Dreams & the Founding of New Hampshire.” This essay is adapted from his book, “New Castle: New Hampshire’s Smallest, Oldest, & Only Island Town.” For more information visit jdennisrobinson.com