Painting the Town of Hinsdale Green

Geoffrey Holt hated spending money on himself so he left his riches to the people of Hinsdale

Edwin “Smokey” Smith holds a photo of former resident Geoffrey Holt

(circa 1970s).

Geoffrey Holt didn’t like to spend money on himself — even if it was something beneficial, says his longtime friend, former state Rep. Edwin “Smokey” Smith.

In his later years, Holt was told by his doctor to elevate his leg often, due to a circulatory problem. But the Hinsdale resident also enjoyed tooling around town in his riding lawn mower, finding different leafy spots to kick back, prop his leg up and read his financial papers.

Smith suggested Holt spend a little bit more to get a comfier ride.

“He always would buy the cheapest riding lawn mower that you could buy at Walmart or Tractor Supply or wherever,” Smith says. And I kept telling him ‘Geoff, if you bought one that’s a little bit more expensive, it would be a little better quality.’ And next thing I know, he bought a new one for the lowest price he could find.”

While he preferred to live thrifty and avoid many creature comforts, Holt had other plans for Hinsdale. In November 2023, the town announced that the longtime resident had quietly left Hinsdale $3.8 million.

Holt’s donation is a donor-advised fund, an endeavor he set up in 2001 with the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation. Holt, who died June 6, 2023, at 82, requested that after his death, the foundation distribute the funds, via grant applications, among four areas: recreation, health, education and culture. As the town can only access $150,000 a year, the funds are designed to last into perpetuity.

Holt preferred his gift stay secret until after his death. Smith guesses the Vietnam veteran, groundskeeper and driver’s ed teacher would probably have been embarrassed by the all the attention his story generated.

A photo of Geoffrey Holt on his mower outside Stearns Park in Hinsdale.

While news reports focused on his “eccentric” nature, Holt was more complicated than his quiet demeanor might have suggested. He was very frugal, and rode his lawn mower around town when he wasn’t taking care of the grounds at Stearns Mobile Home Park, where he lived. He kept to himself, had few friends and was well-educated. He enjoyed reading newspapers and financial reports; and was remembered for carrying a 12-pack of Schlitz beer while on lengthy bike rides to White River Junction, Vermont. He had an extensive collection of die-cast model trains and cars but lived with few niceties.

Smith only had an inkling about Holt’s financial plans or how much money he had saved. But he did notice that Holt preferred to live simply in his small mobile home at Stearns.

“It (had) a woodstove. He very seldom turned the oil furnace on because it cost him money. He got (the wood) himself, and it didn’t cost him anything except his time,” Smith says.

He often relied on his vegetable garden to sustain him.

“Many summers, he’d live on lettuce and tomatoes and summer squash and zucchini, and that’s about it,” Smith says.

Even his clothing went the extra mile.

“When Geoff finished with his clothes, there was nothing left. It wouldn’t even make a good rag — there wasn’t enough material to absorb anything,” Smith jokes.

One of his last pairs of shoes — Crocs knockoffs — remained bargain-basement.

“The only pair of shoes he left was a pair of Crocs from Walmart. But he wouldn’t spend the money to buy a good pair of shoes — even though he had a circulation problem, which would have been helped if he had a little better shoe,” Smith says.

A friend with ‘character’

This was Geoffrey Holt’s residence at Stearns Park in Hinsdale.

Smith met Holt in the early 1980s. After Holt was laid off from his job as a production manager at a Brattleboro, Vermont, Agway grist mill, Smith asked if he wouldn’t mind doing some odd jobs for him at the mobile home park.

Over the years, the two became good friends.

“He was a good guy. He was intelligent, obviously. He was an interesting — and I will use this word — and say ‘character,’” Smith says.

Smith acknowledges that Holt had few friends.

“We used to have some long conversations. But he wasn’t really outgoing. We were close, but we weren’t close. But when we were working together, we talked a lot,” Smith says.

The two shared opposing political opinions — Holt was a Democrat, Smith a Republican — but talk never turned bitter.

“He was a Democrat for sure. And I was a Republican for sure. Our conversations were interesting, but never heated. Neither one of us ever spoke harshly to the other one,” Smith says.

Smith notes that conversations about politics today can quickly turn sour, but their friendship wasn’t like that.

“There’s no compromise — it has to be one way or the other. Geoff and I didn’t have that attitude at all,” Smith says.

Holt also had a passion for voting. His wish list for the town included ballot-counting machines. So far, the town clerk has received about $4,700 for voting equipment through the fund, but it’s not clear whether it will be ready in time for this year’s elections.

From Vietnam to Agway

Geoffrey Lincoln Holt was born in 1941 in Indianapolis, according to his obituary. His father taught English at American International College in Springfield, Mass.; his mother was a painter and a peace activist. Holt attended a Quaker boarding school in Newtown, Pennsylvania, and graduated

with a bachelor’s degree from Marlboro College in Vermont.

After serving in Vietnam with the Navy, Holt earned a master’s degree from American International College in Springfield, Mass., and later, briefly taught social studies and driver’s ed in nearby Winchester. Following his brief teaching career, Holt worked for Agway.

After retiring from Agway when the operation shut down, Holt received a payout and invested the funds, but remained frugal even as the money grew. He lived with his longtime life partner, Thelma Parker, for about 20 years in Hinsdale until her death in 2017.

Holt’s obituary acknowledges his unique qualities, calling him “an intellectually curious, humorous and somewhat eccentric gentleman who made friends easily,” and “demonstrated a knack for understanding market economics.”

Smith got an idea of Holt’s financial acumen through an unlikely source.

“He and his father had a little bit of rivalry over who could pick the best stocks. He told me how much he had. He said the first investment he bought was a mutual fund for communications,” Smith says. “His father told him that that wasn’t going to do anything. Well, according to what he told me towards the end, that was the best performing mutual fund he ever had.”

He later found a letter that confirmed their friendly competition.

“I saw some personal things, a letter from his father to him. And it was saying that this is the stock you should buy,” Smith says. “If I remember correctly, there was a $50 bet in there that ‘I’ll bet my investment in this is going to be worth more than your investment.’ I’ll bet $50. You know, just good-natured fun, that’s all.”

Several news articles incorrectly reported he did not own a television set, Smith says.

“He had several TVs. He did not have a computer. He just figured it was too much of a challenge for him to learn how to use one,” Smith says.

Holt had more than 100 DVDs, some on European history, and enjoyed shows like “The Beverly Hillbillies.” He also had an extensive collection of classical music from European composers.

“His mental capacity was quite a bit deeper than you’d ever believe,” Smith says.

Toy trains and cars are on display inside a shed that houses former resident Geoffrey Holt’s collection.

Smith also remembers Holt’s extensive collection of more than 1,000 diecast cars and trains, some with working doors and hoods.

Over the years, Holt was often spotted riding the lawn mower to Walmart or another nearby store. Other times, he would just sit on it, leg propped up, to watch the world go by. Smith says it also allowed Holt, who didn’t have a car, to travel locally.

“He couldn’t walk because of the circulation. He could get on his lawnmower, and he could ride down to the brook,” Smith says.

Belonging to Hinsdale

With a population of around 4,000, Hinsdale is a quintessentially small New Hampshire town with a unique history, rural charm and welcoming nature.

The town has access to mountains, and there are biking, hiking and camping spots. Local businesses sell their harvest at the annual farmer’s market, and every December a tree-lighting illuminates dark winter days. The town’s website welcomes visitors with the phrase “Live, Work, Play — You Belong Here.”

Kathryn Lynch, Hinsdale town administrator, stands in Town Hall.

When Holt’s donation came to light, town administrator and Hinsdale resident Kathryn Lynch remembers a landslide of news — and a sudden spotlight on Hinsdale.

“It was a shock. It was like winning the lottery almost,” Lynch says. “I don’t think in the history of anything in Hinsdale that we’ve ever been given this ability.”

Lynch recalls how quickly word spread.

“It just kind of all happened in one day. WMUR posted it on the news, and the next thing we knew we had NBC Boston here. We were inundated with many, many newspapers and magazines. It was quite shocking. I had friends and family halfway across the country that were calling me,” Lynch says.

Hinsdale is the kind of quaint New Hampshire town that welcomes stability.

“Hinsdale is an old mill town. Many people have lived here all of their lives, and if they haven’t lived here all their lives, they were born here and came back,” Lynch says.

There’s a beautification committee, a rail trail system, Lions Club, volunteer coaches, a Cal Ripken baseball league, and plenty more that can benefit.

“The town will reap the benefits of this for years because we’ll barely be touching the interest on the account. It’s a very close, nice community,” Lynch says.

Shocking the select board

When Smith went to the select board to tell them about Holt’s donation, they were caught off-guard.

“They were a bit shocked. They didn’t have any idea. Geoff was a pretty quiet person. Nobody knew that he had that kind of money. A lot of them knew him, but they never pictured him for being a multimillionaire,” says Smith, who originally suggested, somewhat jokingly, that Holt donate the money to the town.

“He wouldn’t spend his money on something that he would have really appreciated (for himself). He was interested in doing something with it; he didn’t know what,” Smith says.

Now, about a year after the surprise announcement, about $91,346 has been distributed. The Geoffrey L. Holt Fund will first support the town hall cupola and clock repair, and help reduce farmer’s market vendor fees. The school district has also received funding to support emotional learning and music and dance programs.

“It’s a really tremendous resource for the town of Hinsdale,” says Melinda Mosier, vice president for donor engagement and philanthropy services at the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation. “I think that there’s some real excitement about it. We’re going to start to see some resources from Geoffrey’s gift flow into the community. It’s really, really exciting for people.”

A donation like this is fairly rare. So-called “eccentrics” occasionally make world headlines for their unexpected and large philanthropic donations to the town or region they lived in. The charitable foundation often works with people to establish trusts, but Geoffrey’s donation was unusual.

“Sometimes other people know what’s going to happen. And sometimes like this, it’s a complete surprise, like in the case of Geoffrey Holt,” Mosier says.

She recalled Oliver Hubbard of Walpole, a chicken farmer turned successful businessman and philanthropist. After his death in 2001, Hubbard donated $43.5 million to the charitable foundation to fund treatment programs for those affected by substance use disorder and other addictions.

“Oliver kept his identity anonymous until 10 years after his death, when we had permission to tell his story,” Mosier says.

Hubbard and Holt represent the best of New Hampshire, she says.

“These are gentlemen who lived simply and humbly and in this kind of real, true, Yankee fashion. Oliver built his fortune as a chicken farmer and was really quietly unassuming, in a way similar to Geoffrey was, and then, on their passing, created an enormous benefit to the community that is intended to last forever.”

“The quiet way that Geoffrey went about doing this just reminded me of Oliver. I definitely think about him as somebody who was quietly generous,” Mosier says.

A happy retirement

Smith recalls that Geoffrey’s later years were happy ones. Thelma and Geoffrey spent their retirement years together, visiting his parents in western Massachusetts or going shopping.

Geoffrey and Thelma’s differences kept them compatible, Smith says.

“He was rather shy. And she wasn’t,” Smith says. And he thinks Thelma was good for him, because when she was around, he’d eat a little bit better, and dress in some new clothes once in a while.

“He was brought up to be as conservative as possible. On many occasions, he told me, ‘Thelma, I can live pretty good on just our Social Securities, I don’t have to dip into anything to do it,’ ” Smith says.

Thelma’s death in 2017 hurt terribly.

“He was closest to her than anybody. Thelma was the love of his life, I would dare say. On many occasions, he said, ‘I miss Thelma.’ And it was evident,” Smith says.

Smith misses his companionship as well.

“When I’d go out, he’d always come out. There’s nobody out there now,” Smith says. “I’m a little lonely sometimes.”

Smith says Holt had chairs set up around the property to take in his favorite views. He often visited a special spot alongside Ash Swamp Brook, where he always had a chair at the ready to scroll the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal and enjoy a beer or two. Some of Holt’s ashes were scattered near this site.

As executor of his will, Smith was given all of Holt’s personal effects, including his mobile home, and plans to leave some items and mementos to the Hinsdale Historical Society.

“I’ll try to keep those someplace in the historical society or the town so that somebody else can research him and appreciate who Geoffrey was,” Smith says.

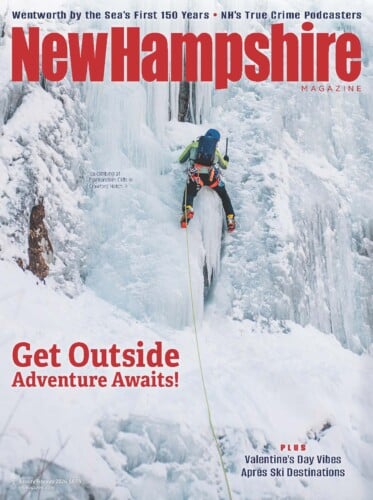

Organizations in town can apply for grants of up to $150,000. Visit Hinsdale’s town website for grant guidelines and applications.