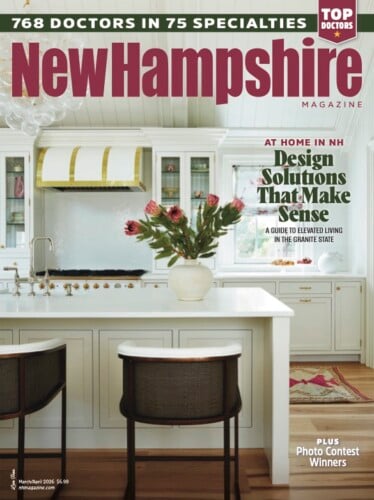

Idyllic Orford on the Connecticut

A textbook example of a New England small town

A place to rest on the parade in Orford. Photo by Stillman Rogers

Orford has changed very little in appearance since 1832, when Washington Irving wrote, “In all my travels in this country and in Europe, I have seen no village more beautiful than this.” Unlike most New England villages, this idyllic center doesn’t circle a common, but lines along either side of a grassy parade. Seven fine Federal homes sit majestically in a row atop The Ridge at one side, while public buildings face them along Orford Street, Route 10.

A good first stop is at the Orford Social Library, housed in a former milliner’s shop in the center of town, to pick up a booklet published by the Historical Society describing the historic buildings and locating them on a map.

Or for the quick version, read the state historical marker that points out the Wheeler House, one of the seven along The Ridge. The home is thought to have been designed by Asher Benjamin, an associate of Charles Bullfinch. All seven of the houses, built between 1773 and 1839, show Benjamin’s and Bullfinch’s influence.

The homes along The Ridge and on the other side of Orford Street are a quick history of the town. Names of the first settlers and their descendants are attached to most of the 38 buildings in the Historic District.

The Orford Social Library is located in the town’s historic Ridge section. Photo by Stillman Rogers

Prominent among those names is Morey, descending from Gen. Israel Morey, one of the original grantees and among the first to arrive here after Orford’s settlement in 1765. In the winter of 1766, he and his family traveled from Connecticut by ox sled, using the frozen Connecticut River as a road from Charlestown north.

Morey donated land for the earliest portion of the common in 1773, to be used for a meeting house and training field. (Orford was chartered by Royal Governor Benning Wentworth as Number 7 in the line of fort towns along the river.) Later grants from landowners secured the southern end in perpetuity to be used as a parade or common and for no other use.

Morey’s son, Samuel Morey, worked at his father’s ferry that crossed the Connecticut River and became interested in the potential of steam power. This interest led him to develop a way to separate oxygen from hydrogen in water, paving the way for the internal combustion engine. History credits him for its invention but not for his other invention, the paddlewheel steamboat, as Robert Fulton duplicitously — but successfully — claimed the patent.

Morey prospered from his inventions, mills and lumbering, and built the house at the center of The Ridge. Three of the neighboring homes were built by store owners, two by lawyers, and one by the manufacturer of beaver hats. Their homes have been called the finest group of Federal-style houses in the United States and are on the National Register of Historic Places.

The grandest of the seven houses is at the southern end, built in 1820 by Gen. John Wheeler. It was Wheeler who provided the money for Dartmouth College to retain the legal services of Daniel Webster when the state tried to make Dartmouth into a state university.

Webster argued that the charter given the college by King George III was a contract and so could not be broken by state action. Webster’s eloquent arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court made the Dartmouth College case a landmark of constitutional law, establishing the inviolability of contracts. Dartmouth expressed its gratitude by naming Webster Hall in his honor.

The 38 listed buildings that make up the Historic District include several 18th- and 19th-century residential and civic buildings facing The Ridge along the west side to the main street. Prominent among them are the brick Masonic Hall, the white Gothic Revival United Congregational Church and the eye-catching Elm House, built in 1798 by Samuel Morey. The current Greek Revival front with column and gable were added in 1849.

The brick Masonic Hall was previously the Universalist Church, built in 1840 and active for about 25 years. From 1878 until it became the Masonic Hall in 1904, it was Union Hall, a public entertainment venue, but through all that time has retained its cupola and other architectural features.

In the mid-1800s, brick was a popular building material for homes as well as public buildings; in addition to the Universalist Church, the 1851 Orford Academy, several houses on Orford Street and two houses on The Ridge are of local brick. The Connecticut River Valley is rich in deposits of clay and sand used in brickmaking, and from the 1770s Orford had its own brickyard on a hillside just outside of the village, off Route 25A.

Orford had two centers — the other one, called Orfordville, a few miles farther east on Route 25A. The 1886 “Gazetteer of Grafton County” lists it with “one church (Congregational), a general store, furniture store, blacksmith shop, school-house, town hall and about seventy-five inhabitants.” The church is worth a stop for its unusual stained-glass windows.

Behind the town hall was a soapstone quarry, one of two in Orford. The largest, on Cottonstone Mountain (cottonstone was an early name for soapstone), was active in the early 1800s and considered one of the best deposits in the United States.

Route 25A curls around the north side of Mt. Cube, originally called Mt. Cuba, Orford’s highest point. The northernmost of its twin summits overlooks Mt. Moosilauke, and the south summit views cover the Connecticut Valley as far as Mt. Ascutney. The Appalachian Trail climbs over Mt. Cube, and the AMC’s “White Mountain Guide” calls it “one of the

more rewarding mountains in the region” for its views. This and several other trails in Orford and Lyme are maintained by the Dartmouth Outing Club.