High Aspirations: Dramatic Tales from Portsmouth’s North Church

Author J. Dennis Robinson tells the dramatic tale of Portsmouth's iconic North Church, and the steeple that shapes the skyline

A night scape shot of a church i found in Portsmouth New Hampshire during a winter night. Photo by apb images

The story of North Church is the story of New Hampshire’s only seaport. In a city without skyscrapers, its iconic white steeple still marks the very heart of Market Square and points the way to heaven.

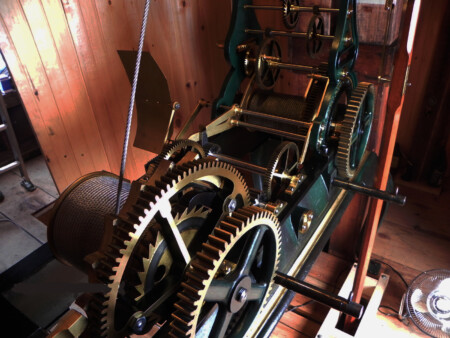

Twice each week, a city employee climbs a series of ladders inside the wooden spire and grasps an ancient brass handle. The handle winds the mighty mainspring that fuels a nest of metal gears and keeps the great pendulum swinging. The church tower is, after all, one giant grand-

father clock.

The oldest item in the North Church archive is from 1640, just 10 years after a ragtag cluster of settlers arrived at Strawbery Banke, later renamed Portsmouth, 3 miles upstream from the mouth of the Piscataqua River. The voluminous records in the North Church collection fill 12½ linear feet of shelf space in the climate-controlled Athenaeum vault just across Congress Street. It is a priceless cache for researchers.

Here Come the Puritans

According to a 1907 church historian, “The Old North Church has had a happy history … No schisms have arisen.” Really? As we’ll see, Portsmouth’s oldest institution split the city in half twice.

Two centuries ago, Nathaniel Adams made it clear that New Hampshire was not Massachusetts. Our English founders, he wrote in 1825, “came not here on account of their religion, but to fish and trade.” That’s not entirely true. The 50 English men and 22 women who founded the Strawbery Banke colony were instructed to mine for precious metals and to set up a profitable fur trade with the Natives. When neither effort panned out, the disgruntled investors back in England shut the company down in 1635, stranding the colonists in a frightening wilderness 3,000 miles from home.

The Strawbery Bankers were a loose collection of God-fearing, self-governing, commercially minded survivors. Most were members of the Church of England — Anglicans, not Puritans. Their drafty chapel, likely built of sawn logs, stood at the base of modern-day Pleasant Street by the South Mill Pond. It operated with one Bible, 12 service books, one pewter flagon and

a single communion cup.

Meanwhile, beginning in 1630, up to 20,000 Puritans were flooding into what would become Greater Boston. Back in England, King Charles I was beheaded as Puritans under Oliver Cromwell took over the government. New Hampshire’s founding towns of Hampton, Dover and Durham fell under Puritan control, while the rowdy residents of Strawbery Banke resisted. Massachusetts governor John Winthrop complained that the people of “Pascataquack” openly defied Puritan justice by sheltering outlaws and heathens.

Although it never gave up its Anglican roots, by 1657 Portsmouth, too, had a Puritan minister. A young Harvard graduate named Joshua Moody would become the rock on which the Congregational North Church we know was founded. Ordained in 1671, Moody is remembered as a popular preacher who drew large crowds to the modest meetinghouse.

With Cromwell dead and the monarchy restored, King Charles II declared New Hampshire to be a royal colony. His appointed governor, Edward Cranfield, lived on Great Island (now New Castle), an Anglican stronghold. Cranfield proved to be hot-tempered and focused on enriching himself. A showdown was inevitable.

“I found Mr. Moody and his party so troublesome that I believed myself unsafe to continue longer among them,” Cranfield reported to the king. In 1684, the unpopular governor locked horns with the popular preacher. Moody was arrested, jailed at Great Island and banished to Boston. Moody later returned, but times were tough. Smallpox, brutal weather, Native reprisals and restrictive shipping laws battered the little seaport. Having delivered 4,070 sermons, Reverend Moody died in 1697.

his rare ambrotype photograph was taken by Carl Meinerth in 1854, the year the brick building was

completed. After the installation of the new city clock, the building was dedicated on Nov. 1, 1855. photo by Carl Meinerth

North vs. South

From 1699 until 1741, New Hampshire was once more under the harsh control of Massachusetts Puritans. Originally dependent on harvesting fish and timber, Portsmouth was becoming a thriving shipbuilding and commercial seaport. In 1704, tragedy struck Nathaniel Rogers, the town’s second ordained minister. A fire at the minister’s house killed Rogers’ mother, his infant daughter and an enslaved African servant. The fire would also change Portsmouth’s history.

A bigger house of worship and a new parsonage were required. Back in 1640, town leaders — all property-owning white men — had set aside a large chunk of land for a future church, almshouse, courthouse and burying ground. Leasing the land, known as a “glebe,” would provide income for the minister.

“Great disorders and tumults ensued” over a plan to move the church inland from the river to what is now Market Square. But when the wooden church opened in 1714, a stalwart group of parishioners refused to move. This first schism split the membership. Rogers, a strict Calvinist, preached at North Church, while Reverend John Emerson took over at “Old South.”

Neither congregation was safe from the fire and brimstone sermons of the era. On Oct. 29, 1727, for example, an earthquake scattered farm animals, cracked buildings and toppled chimneys. Jabez Fitch, then pastor at North Church, blamed his parishioners. The

The North Church has been a Portsmouth institution for over 350 years. A $1.4 million renovation of the building interior is now underway. Photo by Annie Roy

quake, Fitch explained, was God’s reaction to their heavy drinking, sexual deviancy and poor church attendance.

Revolutionary Voices

By the mid-1700s, “a spirit of discord began to appear,” Nathaniel Adams later wrote. Portsmouth citizens rioted against the Stamp Act. They stole 100 kegs of gunpowder from the king’s fort at New Castle and drove royal governor John Wentworth out of town. Just when North Church needed a calming leader, its next minister, Samuel Langdon, quit to become president of Harvard College. Next up, Reverend Ezra Stiles railed against “the great inhumanity and cruelty” of slavery. Yet, Stiles purchased an enslaved boy he named Newport. In 1778, Stiles also left the Portsmouth pulpit to become president of Yale University.

Enslaving Africans as servants, a symbol of social status, was as common among Protestant ministers in the Seacoast region as it was with wealthy merchant aristocrats.

Historian Valerie Cunningham, founder of the Black Heritage Trail of NH, estimates the statewide African population in 1775 was 656, with most enslaved people located in and around Portsmouth.

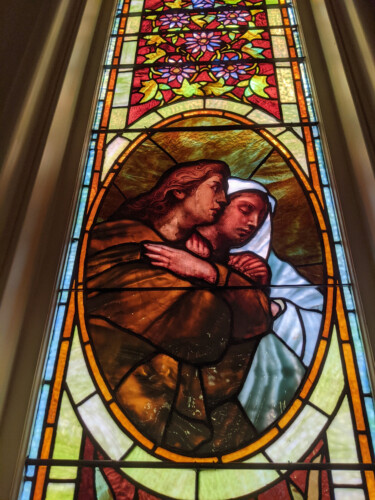

This image is a detail from a stained-glass window added to North Church in 1890. Photo by J. Dennis Robinson

A Healing Break

Handsome, raven-haired Joseph Buckminster is arguably the most beloved pastor in North Church history. His silvery, bell-like singing voice floated above the choir. According to his daughter Eliza, “He could interest people not normally interested in preaching.” Twice a widower and raising two disabled children, Buckminster was a man “of much domestic grief,” Eliza reported.

During the 1798 yellow fever plague — when 156 died in a town of 5,000 — Buckminster spent entire days and nights at the bedside of his dying parishioners. With few newspapers or public reading rooms available, it was typical for the minister to educate his flock about current events. Twenty-five of his printed sermons survive, six of them focused on his hero, George Washington. On Nov. 1, 1789, the pastor was thrilled to welcome the first President of the United States, who attended a packed service at Old North Church in Portsmouth.

Reverend Buckminster and Samuel Haven, the popular South Parish minister, were close

Esther Mullinaux, daughter of the enslaved Prince and Dinah Whipple, joined the North Church in 1801. Courtesy Portsmouth Athenaeum

friends. But their deaths, the War of 1812, three devastating downtown fires and a plunging maritime economy took their toll. Young Portsmouthites began moving to bigger cities and westward in search of income and opportunity.

The Brick Church

Israel Putnam inherited the North Church pulpit in 1812. His hardline views led many parishioners to “migrate south” to the more liberal congregation of Nathan Parker. Then in 1819, Parker crossed the line when he introduced “Unitarian Christianity” at Old South Church. Unitarians openly questioned the Calvinist view of Original Sin, the Fall of Man, the Holy Trinity and the duality of Jesus Christ as both man and God.

It was a holy war and a second schism. With his membership waning, Reverend Putnam labeled Parker an “infidel” and a “subversive.” Adding fuel to the fire, Parker’s crowded congregation voted to leave their church by the river and move downtown. They built a Greek Revival church from sturdy Rockport granite barely a block behind the aging wooden North Church.

This engraving of Joseph Buckminster, the beloved North Church pastor, was adapted from a portrait attributed to John Trumbell. Courtesy Portsmouth Athenaeum

Putnam saw the future. His deteriorating wooden North Church, he said, was “exceedingly repulsive to the minds of the young and strangers.” Besides the loss of members to Unitarianism, Putnam’s congregation was now competing with local Methodists, Baptists, Episcopalians and a Sandemanian Society.

When 40 more members broke off to create a separate Congregational group, unable to raise funds for a new building, Putnam resigned in 1835. Lacking money to rebuild North Church, Pastor Edwin Holt, a pro-slavery advocate, then raised $5,800 for a major renovation. His successor, Henry D. Morgan, finally banked the $24,000 needed to start over.

Spectators packed Market Square as a rigger tied a rope to the peak of Old North. “Many willing hands,” the newspaper reported, hauled on the line as the spire, the clock having been removed, crashed to the street below. Construction of a new brick building took two years.

In the interim, North Church members met at “The Temple,” a former Baptist church and today the site of the historic Music Hall. The costly wooden spire was funded by the city to house a new downtown clock. “Do this as cheap as you can,” the mayor of Portsmouth requested. The building we know today was dedicated on Nov. 1, 1855.

Victorian Portsmouth

Finding funds to pay any minister was a constant struggle. Ironically, a large swath of downtown real estate had once belonged to the church. Early renters leased land in the North Church “glebe” for 999 years. But payments faded after the Revolution. Too bad, Charles Brewster wrote. As a 19th-century editor of the “Portsmouth Journal” and a North Church member, Brewster calculated the loss. Downtown businesses, he joked, would owe the church billions of dollars in overdue rent.

The lack of funds for a settled minister, however, never slowed the outpouring of charitable

work. Over a dozen North Church groups, led almost entirely by women, served the community well. Volunteers ran a school for girls, youth groups, missionary societies, Bible study, support systems for mothers and more. The Ladies Box Club raised funds to build a nearby parish house, later the Salvation Army, and today a hotel.

“The Old Town by the Sea,” meanwhile, was becoming a popular summer tourist destination. Trains, trolleys and ferries whisked visitors from hot and polluted cities to the breezy seaside resorts of nearby Rye, New Castle, Kittery, York and the Isles of Shoals.

Through the 20th Century

Like a giant grandfather clock, the massive pendulum swings inside the North Church steeple. Photo by William S. Roy

Looking back, the arrival of Rev. Lucius Thayer in 1890 seems providential. His 38-year tenure anchored the North Church community for the first time since the days of Joseph Buckminster. “He spoke quietly, but with conviction,” a parishioner recalled, “obtaining power not through external fireworks but through the substance of his teaching.”

A massive pipe organ, a new town clock and stained-glass windows arrived during this era. Thayer provided comfort during World War I, welcomed the city’s first Jewish temple and reached out to immigrants from “Little Italy” in the nearby North End.

He seemed to befriend everyone in town. By his retirement, Thayer had presided over 1,059 funerals and counseled 678 couples.

From tall ships to nuclear submarines, Portsmouth had become a blue-collar military town. The North Church congregation swelled with the arrival of Pease Air Force Base in 1954. The city center, meanwhile, was battered by urban renewal, clogged by motor traffic and drained of commerce by encroaching shopping malls.

In 1962, Rev. John Feaster dedicated a new parish campus a mile and a half from the brick church in Market Square. The alternate site offered a nursery, expansive kitchen, reliable heating, sunny windowed rooms and parking for 150 cars. Locals called the modern design “Father Feaster’s ski lodge.”

Save Our Steeple

The 19th-century mechanical clock in the North Church is wound by hand twice per week by a Portsmouth city employee. Photo by J. Dennis Robinson

As North Church members settled into their new parish house, the city center began a period of growth not seen since George Washington’s visit. The revival included Theatre by the Sea, Strawbery Banke Museum, trendy restaurants, a tourist-friendly streetscape, annual festivals and tall ship parades. Portsmouth became a “must-see” heritage destination. Travel ads inevitably featured the gleaming white North Church steeple.

In 2003, church caretakers spotted water stains at the rear of the sanctuary. The “lantern room” above the belfry, built in 1863, was leaking badly during storms. Creeping damage had taken a heavy toll. “The steeple is our Eiffel Tower, our Big Ben,” the Portsmouth Herald editorialized. “One cannot imagine the horizon without it.”

The 330-church members, led by Rev. Dawn Shippee, raised $500,000 to launch a herculean repair job. Community volunteers raised a million dollars more. Soon a metal framework encircled the nearly 200-foot-tall structure. Then in July, during a severe thunderstorm with high winds, portions of the worn and rotted spire, along with its surrounding metal scaffolding, plummeted to the street below. Miraculously, no one was harmed. By 2007, free of its metal frame and freshly repainted, the beloved church tower was back, topped by its restored 18th-century weathervane. Portsmouth was Portsmouth once more.

Future Tense

In 2015, Reverend Shippee reflected on her career at North Church. “In terms of worship,” she said, “it’s a beautiful space. It’s a fairy-tale church. But church is about people, not about buildings.” The most impressive part of restoring the steeple, she said, was watching the community come together. An even more dramatic event, Shippee said, was allowing the United Church of Christ (UCC) to open its doors even wider.

Today the organization’s website declares: “We embrace people of any race, creed, color, age, gender identity and gender expression, sexual orientation, economic status, marital status, physical, emotional, mental capacity and those in relationships recognized under God’s law.”

Congregational church membership, however, has declined across the nation. Portsmouth hovers at around 120 members, predominantly senior citizens. Following COVID-19, the decision to sell the parish house complex did not come easily. In 2022, the Islamic Society of the Seacoast Area purchased the Spinney Road site for $2.7 million. Funds from the sale are being used to provide the historic downtown church with office space, a meeting room and kitchenette, restrooms, energy and accessibility upgrades and more.

Today, Reverend Jennifer Mazur finds beauty in the congregation’s courageous return to Market Square. Sunday attendance is up 50%. Two couples with young children have joined.

“When churches shrink, they’re forced to think about what life to take on next,” Mazur says. “What future is waiting for them? North Church is making a courageous choice to be where the people are and to use their resources to benefit the community. I don’t see us diminished. I see us as being changed. What is there to do now but to be a voice for love and justice?”

It’s been a long journey from the Bay Psalm Book to Zoomed church services. A century from now, we can only hope that a city worker will still make the biweekly trek up the steeple stairs to wind the town clock by hand. A bell will chime. An ancient weathervane will shift in the sea breeze. The doors will open and a small congregation with a big heart and a rich history will gather in love and faith once more.

J. Dennis Robinson is the author of 20 history books, including “A Brief History of North Church.” His latest work includes “1623: Pilgrims, Pipe Dreams, Politics and the Founding of New Hampshire.” His new history mystery novel, “Lucy’s Voice,” centers around the Lincoln assassination. For updates, visit jdennisrobinson.com.