Building with a Beanpole

Laborers who worked on a hydroelectric project in Marlborough a century ago relied on simple technology for complicated measurements

Raise your hand if you ever had to stand up in front of your elementary school class and read or recite from the poem, “The Song of Hiawatha” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Now raise your other hand if you can remember any portion of the poem other than, “On the shores of Gitche Gumee.” I vaguely recall the line, “at the door on summer evenings, sat the little Hiawatha; Heard the whispering of the Pine-trees, heard the lapping of the water…Minne-wawa! said the pine-trees.”

I’m reminded of this poem because I’m at the Minnewawa Hydroelectric Project on Minnewawa Brook in Marlborough. There are dissenting opinions on the interpretation and meaning of “Minnewawa” or “Minnehaha.” Some say it comes from the Ojibwa language, and the English translation is best described as “laughing waters” or “babbling brook.” Others believe it originates in the Dakota language and means “waterfall.”

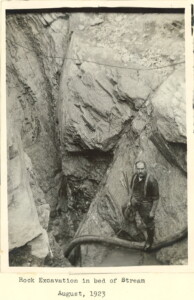

A muddy workman mans the mud section hose as the team removes drilled rock where the to-be constructed bypass spillway will go around the dam.

This hydro project was constructed 100 years ago and included a dam built in an isolated part of Marlborough with a powerhouse constructed over a mile away. Water from the dam flowed through a 4-foot

diameter penstock down to the powerhouse, where the torque of the falling water spun turbines and generated electricity before returning to the brook. The penstock, constructed of redwood staves and held together by iron rings, was supported every 10 feet on a concrete cradle foundation.

Adventurous neighborhood kids walked the top of the penstock as a shortcut to the dam for fishing and swimming. A misstep meant a fall onto exposed ledge, and parents viewed this as dangerous. Kids, however, viewed it as a challenge and a rite of passage to test their mettle. Today, the wooden penstock has been replaced with steel pipe and is mostly below ground, eliminating the dangerous shortcut.

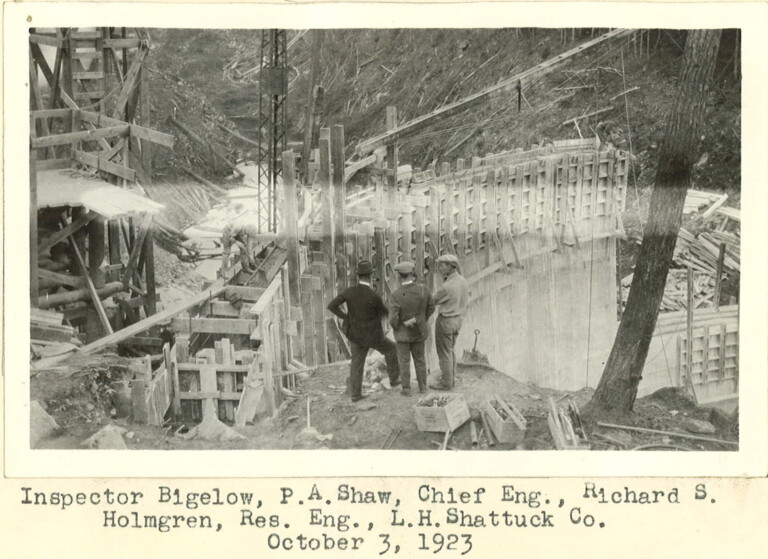

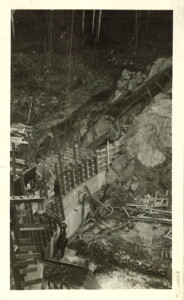

Worksmen construct wooden concrete forms on top of a previously poured concrete tier in anticipation of pouring the next tier of concrete.

The Minnewawa dam is constructed of solid concrete, 200 feet long, and rises some 55 to 60 feet above the streambed in the narrow but deep gorge. With its tall vertical face gracefully bending out into the impoundment, the dam is both aesthetically pleasing and an engineering masterpiece.

This dam was constructed in 1923 some 13 years before the similarly curved Hoover Dam was built. It is 14 feet wide at the base and 5 feet wide at the top. While the upstream face maintains a straight vertical line from bottom to top, and a constant radius of 85 feet, the downstream face tapers and leans in to the upstream face, creating the appearance of a large ice cream bowl.

I’m baffled as to how the construction crew, using 1920s technology, was able to perform the complicated measurements required to position the concrete forms along this sloped and curved face. Accurately laying out the arc of a curve while working at the bottom of a steep gorge must have been a challenge. I’m also wondering how they were able to reach across this chasm and pour concrete into the far distant forms before the days of cement trucks and concrete pumpers. Fortunately, the answers are revealed in some dynamic photos taken during construction.

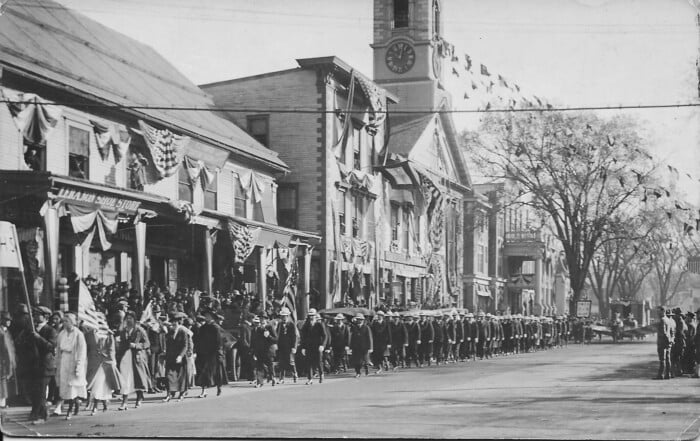

The pictures show that a temporary railroad siding was constructed into the site so that supplies could be brought in by train — although a mule pulling a dump cart also appears in one of the photos. Long homemade wooden ladders lean precariously down the cliffs into the bottom of the gorge. Sandbags are stacked to divert the flowing water around the active construction. A smoking boiler suggests steam may have powered rock drills, pumps or cable winches.

Tall temporary towers are erected on both sides of the gorge and then interconnected with a series of cables and guy wires. Suspended from these cables are gutsy laborers hanging in baskets or simple plank staging. A stationary derrick lifts giant buckets of concrete from the ground to the top of the tower where it then flows downhill through a series of zig-zagging downspout troughs and funnels into the waiting forms. There are no safety railings, safety nets or harnesses, and straw skimmers, fedoras and newsboy caps replace hard hats.

My answer to their puzzling ability to make complicated and accurate measurements is hidden in the background of some of the photos. They used a beanpole. Some 85 feet downstream from the dam they erected a very tall pole equal in height to the top of the proposed dam. This beanpole is positioned at the exact radius point for the arc of the dam and is graduated in feet and inches. A staging tower encircles the pole allowing a laborer holding the dumb end of a long tape measure to reach any elevation on the pole.

If the beanpole is plumb, a level measurement of 85 feet will always be to the upstream face of the curved and sloped dam. The downstream face can be calculated knowing the graduated elevation mark on the beanpole and the tapering thickness of the dam at that elevation. A simple solution dreamed up by someone cleverer than me, with no fear of heights.

Today this hydroelectric facility is owned by Ashuelot River Hydro Inc., and I’m at the powerhouse with Bob King, the company president and majority owner. Bob graciously shows me around the facility and demonstrates an uncanny ability to answer my tough questions before I’ve even finished formulating them. I learn that they produce enough electricity here in an average year to power almost 1,000 homes. Unlike solar panels, hydroelectric facilities can produce electricity at night or when it is raining, and they do not create pollution by the burning of fossil fuels.

Bob tells me that, when his company acquired the facility in 2013, it was in disrepair and required some significant renovations and upgrades. This included a major repair to the 1923 dam as the concrete was spalling and flaking away due to weathering and age. So, in 2016 the old dam was resurfaced with a fresh new concrete face, and now the Minnewawa Dam on the laughing waters brook should be good for another 100 years. And any of you still thinking about Longfellow’s Hiawatha poem can put your hands down now.