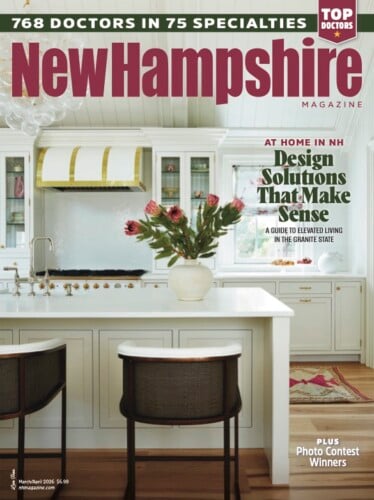

Saddle Up: On Man’s Dream Becomes a Polo Partnership That’s Not Horsing Around

UNH Wildcats and Kingswood New England Polo & Equestrian gallop to success

Federico “Fede” Wulff had a dream. This past fall, as his piercing blue eyes gazed across his Kingswood of New England Polo & Equestrian facility in East Kingston, watching princely horses trot through the bucolic setting, the 40-year-old native of Argentina realized his dream was now a reality.

“The concept of our business is to follow our passion,” Wulff says. “I know for sure that we and the entire Kingswood family are doing this for the right reasons.”

The serene setting, though, was soon replaced by controlled mayhem, as the women’s polo teams from the University of New Hampshire and Skidmore College squared off at Kingswood’s cavernous indoor arena. For Wulff, that dichotomy is the very nature of polo.

“For me, polo is the most difficult sport in the world,” he says. “It combines a unique connection with the horses, endless strategies, teamwork and lots of work and training behind the scenes.”

UNH Wildcats, from left, Jamie Sherman, Heidi Goodwin-Wienges, Catherine Ling, Ariadne “Ari” Dogani and Rebecca “Becca” LaFrance flank their coach, Federico “Fede” Wulff.

While Kingswood may be the culmination of Wulff’s vision, there’s little question that he and this impressive facility have launched many more dreams — reviving a moribund horse farm, establishing a first-class equestrian and polo facility, and enabling UNH to launch a successful women’s polo program in 2024, while also absorbing the polo programs at Babson College.

“Fede is instrumental in both Kingswood’s and UNH polo team’s success,” says Ariadne “Ari” Dogani, captain of the UNH polo team and a senior in the Animal Science: Equine Industry and Management program within UNH’s College of Life Sciences and Agriculture (COLSA). “Without his management of horses and people, his personality, his knowhow, his horsemanship, and his exceptional ability as player and coach, our UNH polo team would not have been able to rise to prominence in such a short time.”

Wulff has coached the Babson teams since 2022 and recently took over the reins of the UNH team from Kingswood assistant manager Ernesto “Rulo” Trotz. Like Wulff, Trotz hails from Buenos Aires, Argentina. He first came to the United States with his father, a professional polo player, and then relocated more permanently eight years ago to pursue his own polo career. He has played with Wulff and was impressed with his countryman’s devotion to his profession.

“When Fede created Kingswood, I told him, ‘Don’t leave me out of this. I want to be a part of this,’ ” Trotz says. “I saw the potential that the place had. Federico has a lot of imagination, a lot of plans and a lot of projects. I wanted to work in a place like that.”

Wulff arrived here in 2002 to play polo professionally (he is a three-goal-rated professional; five goals indoors) and work as a trainer. The Kingswood location in East Kingston, he says, is ideal, “close enough to the city of Boston. But, the number of schools and universities is also great for upcoming polo players.”

The 180-acre operation is an equestrian utopia, offering boarding options and riding instruction for all ages. During the winter, Kingswood houses between 40 and 60 horses, and that number increases to more than 100 during the warmer months. Similarly, Wulff’s staff of five during the winter expands to 10 in the summer. The property, by equestrian standards, is immaculate.

“The Kingswood facility is state of the art,” says Claira Seely, assistant professor with UNH’s Department of Agriculture, Nutrition, and Food Systems, and faculty advisor to the UNH polo team. “I can safely say it is one of the nicest horse barns I have ever been in.”

UNH senior Catherine Ling charges toward the goal in front of the viewing stands at Kingswood New England Polo & Equestrian.

As the farm’s name suggests, Kingswood’s priority is polo, embodying Wulff’s vision of establishing a world-class program in New England. But Kingswood needed more than a vision; it required a serious financial investment and plenty of elbow grease. Work began immediately after Wulff purchased the dilapidated property in June 2022, with a full renovation of the existing stables and barn, barn bathroom and temperature-controlled tack rooms, the addition of 18 stalls in a second barn, 14 outdoor paddocks and 30 outdoor stalls, plus a new outdoor polo field and outdoor practice area.

The center stage at Kingswood is the facility’s indoor polo arena. Insulated and illuminated with LED lighting, the arena features an elevated, heated viewing deck with linen-covered tables for spectators, two new bathrooms, dressing rooms and a players’ lounge that showcases the trophies won by Kingswood-affiliated teams. Spectators — typically family members and friends — set up tables of food and other refreshments, giving the deck a true tailgating feel.

“The atmosphere we’re trying to create is that you can spend the whole day here,” Wulff says.

But creating an inviting space, and drawing new polo fans, meant dispelling misconceptions about the game.

“Many people do not try the sport because they think it is too exclusive,” Wulff says. “We try to attract as many new people as possible and guide them through it, showing them that there’s always a way.

“There is much more to the sport — the love of the animals, the lifestyle, how healthy it is for families to be involved in such an amazing environment,” he says.

Wulff established an interscholastic program for young players ages 12 to 18, an intercollegiate program that currently hosts UNH and Babson, a club polo program for Kingswood members and a coaching league program for beginners. During the summer, Kingswood offers similar programs outdoors, and Wulff plans to host tournaments every Saturday to increase exposure.

“We want to make a difference by making sure people know that this place is for everybody,” Wulff says. “The gates are always open.”

The lure is the expertise that Wulff, Trotz and other staff members bring to the Kingswood programs, and the quality of the amenities.

“We have the facilities, and we’re waiting for more players to get involved, new people that are not from the sport and want to see what it’s about,” Trotz says. “And I guarantee that everybody, every person that comes, they get hooked.”

Wildcats with mallets

Shortly after purchasing Kingswood, Wulff welcomed the Babson College men’s and women’s polo teams. His plan for hosting collegiate programs was elegant and affordable. Kingswood provides the ponies, including their care and boarding, the facilities where the teams can practice and play, and any necessary coaching. The schools produce the players and a portion of the required finances.

“We offer a premium service for riders,” Wulff says. “Colleges usually have a hard time figuring out ways to afford their polo program. There are too many expenses and responsibilities, so eventually their efforts wear off and their level of horses gets weaker.

“We’re a third-party provider, and (the schools) don’t have to think of anything,” he says. “Kingswood offers sustainability. You only succeed by growing the program. You have to keep growing.”

The seamless integration of the Babson teams paved the way to establishing the women’s polo program at UNH. Driven in large part by Dogani and her parents, Wulff offered Kingswood as the team’s home base, but the idea still took several years to reach fruition.

“Polo isn’t just another college or club sport,” says Dogani, 21, of Brookline, Massachusetts. “Besides the players, it requires a college recognition as a college sport, a faculty sponsor, team formation documents, a regulation polo arena, strings of trained polo horses, a polo coach and funding for a budget to maintain all of the above. With the support and persistence of the leadership of COLSA, the UNH Foundation, and the United States Polo Association, we found a way to combine our team’s enthusiasm, Kingswood’s expert coaching and polo resources, and launched the team for the 2024-25 season.”

According to Wulff, the ongoing support and financial investment of the Dogani family “has been essential with everything at Kingswood.”

“They believe in my dream and vision, and from there, the journey began,” Wulff says. “We say to each other: This is two families sharing a dream, and we need to make sure this concept is what other people see so we can make the polo family bigger.

“The Doganis thought how important it would be to add another equestrian sport to UNH,” he says. “The rest is history.”

The UNH team immediately established themselves as a force, reaching the finals of the U.S. Polo Association Women’s Division II National Intercollegiate Championship last spring before losing a heartbreaker to Cornell University in overtime. The Wildcat crew benefited from the veteran leadership of Dogani and Brynn Roberts, a senior nursing major who was a member of Dogani’s high school polo squad.

However, teammates Catherine Ling and Rebecca LaFrance were new to the game. Though both are skilled equestrians — they compete for UNH’s Intercollegiate Horse Shows Association team — Ling and LaFrance soon realized that polo, and adapting to polo ponies, was a very different proposition.

“My initial attraction to the sport after playing a few times was the speed. I loved when there was a breakaway in a game or practice, and I could just explode after the ball or the other horses,” says Ling, 22, of Wolfeboro. “I was also so impressed with the horses and their training. They are so unlike the horses that I am used to riding, you’d think they are a completely different species.”

UNH freshman Heidi Goodwin-Wienges catches a breather during a rare break in the action in the Wildcats match against Skidmore.

One of the time-honored beliefs among polo players is that the ponies are the true athletes on the pitch. Riding techniques, Ling says, “are completely different on the polo ponies, which was a bit of a learning curve.”

“But once I started to understand, there was almost no limit to what you could ask them to do,” she says. “They can rock back on their hind end and pivot on a dime with just a light shift in your seat and guiding motion with your hand.”

LaFrance, a 22-year-old from Berwick, Maine, fortuitously met Dogani her freshman year. By her junior year, she was on the team.

“The adrenaline from playing and the combination of riding horses, which I had already had a deep love for, and playing a team sport made me love the game,” says LaFrance, a senior studying psychology.

Trotz, who coached the UNH team last year, says a key ingredient is matching ponies with players based on ability.

One significant hurdle for the UNH newcomers “was to actually grab the mallet properly and be able to hit the ball properly,” Trotz says. “That was the biggest challenge, because all the riding skills that they already have makes it much easier to learn. They already have the foundation; that is the riding.”

This year, the team welcomed two new players — sophomore Jamie Sherman of Brimfield, Massachusetts, and freshman Heidi Goodwin-Wienges of Hope, Maine — both of whom have years of riding experience but no polo background.

“I came into the sport never having played a day in my life, and was a nervous wreck,” Goodwin-Wienges says. “Federico has always been so supportive and patient and has been the best coach I could ask for. Polo can be very intimidating, but I know I’m being taught by the best.”

The ponies at Kingswood, she adds, “are absolute beasts, and are the most athletic and powerful horses I’ve ever sat on.’

“I’ve never ridden horses who enjoy their jobs so much,” says Goodwin-Wienges. “They are treated with so much respect by everyone at Kingswood.”

Dogani says those ponies are “the essence” of the Kingswood programs.

“Without them, nothing would be possible,” she says. “Fede, like all dedicated polo players and horsemen, defines himself by the quality and condition of the horses. After all, horses account for more than 70 percent of the success of every player.

“Horses are the ones that allow a good player to shine,” Dogani says. “The fact that we use top quality horses allows all our players to perform better, learn easier and progress quicker. Not all programs are as lucky. Most college programs must make do with donated older horses or retired horses, and that makes it harder on both the players and the horses to perform their best.”

The players, however, also acknowledge that the overall success of the program depends on more than ponies, quality coaching, and the facilities. In addition to praising Seely in her role as faculty advisor, Dogani credits Sue McDonough from the UNH Foundation as being “a force behind the scenes getting UNH to support us.”

“She was one of the first people at UNH that recognized the benefit of having a polo team,” Dogani says. “Polo is a lifelong sport, and college polo creates a great opportunity for alumni to stay engaged with the school.”

Seely, conversely, says the lion’s share of the recognition belongs with the players.

“The dedication by the team members and unwavering support of one another is incredibly valuable,” Seely says. “In their first season, only two of the girls had played polo before, but that didn’t stop them from playing collaboratively and doing incredibly well.”

At the beginning of 2026, the UNH women had already qualified for the Northeastern Regional Championship, which will be held at Kingswood in mid-March. Home turf. Just the scenario to inspire new dreams.

For details on programs offered at Kingswood of New England Polo & Equestrian, visit kingswoodpolo.com.

Hockey on Horseback

Members of the UNH and Skidmore College polo teams celebrate a spirited match. From left: Ariadne “Ari” Dogani, Nora Jackson, Heidi Goodwin-Wienges, Charlotte Wilkes, Rebecca “Becca” LaFrance, Eleanor King, Jamie Sherman, Val Chervinskaya and Catherine Ling.

As an equine pursuit, polo is an agility-oriented, adrenaline-fueled discipline that combines “the highly technical, careful, and structured showjumping routines with free-flowing and improvisational riding that must be adapted to every play,” says Ariadne “Ari” Dogani, captain of the UNH polo team.

“I started, like most people who have no family or background in polo, by playing arena polo,” she says. “Arena polo teaches you the basics without requiring significant investment in horses and is particularly accessible to prospective players in the Northeast, especially during the winter.”

Polo is often referred to as “hockey on horseback,” and indoor, or arena, polo takes that comparison to the next level. The game is played in a venue that looks like a hockey rink, without ice.

At Kingswood of New England Polo & Equestrian facility in East Kingston, the arena measures roughly 300 feet by 100 feet, enclosed by boards to keep the ball in play. There’s even a Zamboni-like groomer that levels the sand-covered pitch at halftime (outdoor polo, meanwhile, is played on grass, which led to the wonderful tradition of spectators “stomping divots” at halftime).

The indoor game has obvious similarities with outdoor polo. Both versions feature polo ponies and mallet-wielding players. The object is still to put a small ball into the goal, and to do that more often than your opponent. But there are distinct differences.

The outdoor goal is typically 8 yards wide, while the indoor goal is between 10 feet and 12 feet wide. The outdoor field is enormous — the size of nine football fields. The much smaller arena means each team has three pairs of ponies and players instead of four, and the game itself is shorter, consisting of four chukkers of seven minutes each (rather than six to eight chukkers outdoors).

Those variations mean the players require fewer ponies — two to four for indoor polo compared to six to 10 or more for outdoors. That allows Kingswood to provide ponies for visiting teams (the teams switch ponies during the match to ensure fairness).

The indoor ball is also different. Unlike the hard, solid plastic ball designed for long passes and shots, the arena polo ball, while the same size, resembles a mini-soccer ball, softer with a bladder, to prevent injuries (while also creating rebounds off the boards, changing tactics).

While outdoor polo is defined by speed, more spacing with long passes, elegance and endurance, arena polo is better known for its rough-and-tumble nature, a physicality that demands quick reflexes and tactical rebounds.