In Their Own Words… with Mel Allen

Editor and writer Mel Allen collects some of his most memorable stories for “Here in New England”

Mel Allen has spent nearly a half century searching for stories in New England that otherwise might never be told — at least not in the way he commits to telling them. These are stories crafted from asking endless questions and listening quietly for the answers, often from people who are trying to convey the very essence of their lives.

“Here in New England” collects more than four dozen of these stories, culled primarily from Allen’s 45 years at Yankee, where he served as editor for nearly 20 years until retiring in January 2025. We sat down with Allen at New Hampshire Magazine to talk about the book, which he arranged thematically in chapters like “The Ways We Love” and “Courage and Resilience.”

Anyone who appreciates great storytelling will witness the narrative sweep, the attention to detail and the quest to magnify the heart and soul of each person Allen encounters.

All of the stories in some way connect people, the Peterborough resident says, sometimes by tragic circumstances.

“The Day Kurt Newton Disappeared,” about a boy who vanished from a Maine campsite in 1975, comes from the “Hard to Forget” section.

“Everybody can relate to what it would be like to be searching for a 4-year-old child who’s missing,” Allen says.

He first met the boy’s parents while working on a story about the search for the Maine Sunday Telegram. He visited with them four years later for one he wrote for Yankee.

“The search for Kurt Newton united the entire state of Maine,” Allen recalls. “There were factories shut down. Most people did not know the family, but they came. They had to search for this kid.”

The Sunday Telegram story was published before Allen started working for Yankee. It was an apprenticeship that didn’t pay much, but it taught him how to hustle.

“When you’re a freelancer, you go after every possible story,” says Allen, who was paid $150 for a 3,000- to 4,000-word story — less once he deducted the $30 he spent on lodging, food and gas.

“But I was learning, and it gave me a portfolio so that when I came to Yankee to show my stuff, I had a pretty good portfolio,” he says.

Another Sunday Telegram story that appears in the collection is about a fellow writer named Stephen King, whom Allen met in 1976 when they lived a few miles from each other in Maine. Allen’s assignment in 1979 was to shadow the horror author upon his return to the high school where he taught English before “Carrie,” Salem’s Lot” and “The Stand” propelled him to bestseller fame.

Later that same year, when King published “The Dead Zone,” he included a character named “Mel Allen,” a reporter for the “Press Herald.”

“I doubt there’s anyone else who can say they not only helped Stephen King round up pigs, but who also became a character in one of his books,” Allen says.

Tragedy and triumph

Allen titled his 1982 tale about racing sled dogs “The Worst 30 Minutes of My Entire Life.” Courtesy Photo

With the opening paragraph of “Taking the Wheel,” a 2019 story about a young woman who takes over as captain of a tour boat for her ailing father, Allen reveals what drives his muse:

“Sometimes one person’s story can seem to contain the whole of human experience — tragedy and triumph, despair and resilience, dreams dashed and dreams made real.”

It’s one of the stories Allen chooses to bring up during our talk, during which he launches into storytelling mode.

“I think everybody might be able to relate to Anna Milne, whose father was the captain of a tour boat in the Thimble Islands (in Connecticut) for many, many years. Everybody knew him from the time she was a little girl… She used to ride in the boat listening to her father. You know how they do those spiels in the tour boats? They’re funny, but informational.”

After Milne’s father was in a motorcycle accident and suffered brain damage, she pledged to take his place, learning how to navigate the waters from other local tour boat captains.

“She had these hopes … None of them had to do with running a tour boat, but she didn’t want to let her father’s life kind of just end that way,” Allen says. “All the other tour boat captains who were competitors took on his tours that summer, while she learned how to be a tour boat captain.”

It’s the kind of story where the happy ending is bittersweet. Something is lost; something is gained.

Allen enjoys a walk along the beach in Ogunquit, Maine, with Rudy, his dearly departed Jack Russell terrier. Photo by Annie Graves

“This is the kind of stuff that I’ve been drawn to,” Allen says, with all the enthusiasm of a cub reporter new on the beat. “When you tell a story, you want to have a beginning, a middle and an end. You want to have surprises. You want to have people who have to overcome some incredible obstacles. This book is filled with those. I left out more, far more, from my 45 years than I have in this book.”

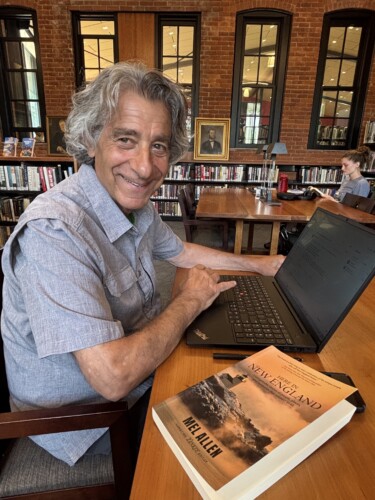

Allen still spends several hours a day hunkered down at the Peterborough Town Library, so it’s not surprising to learn he was meticulous in how he chose the stories that would make up “Here in New England.”

In early February, in Vancouver, British Columbia, he met his two sons, Dan, who lives in Hawaii, and Josh, who lives in Colorado, for a skiing trip. His sons grew up in New Hampshire and are expert skiers.

“I am not, and I didn’t even put my feet into ski boots. What I did is every day was walk to the ski lift to the gondola,” Allen says.

That’s where he would say goodbye to his sons for a while. It was time to gather stories for his book at a nearby library in the village.

“I had note cards I bought at Staples, like about 200 note cards. I wrote down the titles of all these stories. I brought with me a folder, probably 80 printouts from stories, and on the note cards I put titles,” Allen says.

What stories would people really want to read now?

Allen started seeing themes emerge as a way to arrange the book, with the end result being a collection that could stand

as more than just a random series of unrelated stories.

And if he sounds just a bit proud about the result, he’s worked a half-century to earn that right.

“These aren’t favorites. These are ones that I thought worked together, almost like if a chef was doing an incredible banquet. Every dish might not be his favorite dish, but they work together for the flavor.”