Redstone Remains: The Abandoned Quarry Lies Hidden in the White Mountains

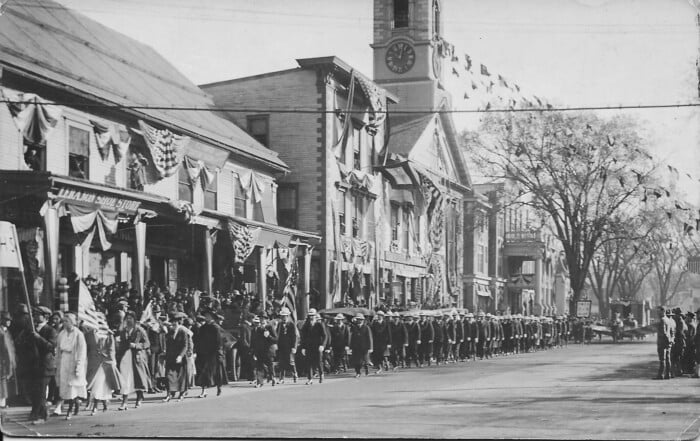

The Conway village was built as a company town for a granite quarry business

The rattlesnakes are now long gone, but their legacy remains. I’m exploring the woods on the southwest side of Rattlesnake Mountain in Redstone, NH. Rattlesnakes were once hunted here and sold for their venom, which was valued for medicinal properties.

This practice stopped about 1870, when a forest fire raged over the mountain, killing off the snake population, but leaving the dangerous-sounding name behind. Tragic for the snakes but good news for me, as I’m looking for the abandoned Redstone quarry, and not desiring to run into any rattlers.

Redstone is now a village within the town of Conway, but its origins are of a company town built by the Maine and New Hampshire Granite Company, which operated a quarry on the side of this mountain. During its boom years, Redstone had a boarding house, schoolhouse, church, poolroom, dance hall, company store, railroad station and some 20 houses for the employees.

This lathe that dwarfs Marshall Hudson was capable of rotating large chunks of granite at high speeds.

The village had its own post office and boasted a population of about 300 people. Most residents were employed at the quarry or in an occupation that directly supported the quarry laborers or their families.

The quarry operated from the late 1800s to about 1948 and produced granite desired for its unique red-brown color, which resulted in both the quarry and village being named Redstone. An adjacent part of the quarry produced a stone with a green tint, meaning clients could also get green stone from Redstone.

Besides the two sought-after colors, the stone was uniform in composition, split easily and was soft enough for carving and etching, but hard enough to be durable and long-lasting. A railroad spur line ran into the quarry making it possible to transport Redstone granite anywhere reachable by railroad. In the late 1800s, Redstone flourished as granite was in great demand for block buildings, foundations, paving stones, memorials, carved statues, bridge abutments and railroad culverts.

As I rounded a corner in the trail, I came upon the first clue that I was getting close to the old quarry site. On the side of the trail, there was a large round granite column about 20 feet long and big enough in circumference that two people holding hands would have to stretch to reach around it.

Someone had polished the column as smooth as glass, and it looked like it should be holding up the dome of some capital building instead of laying discarded alone in the woods. Looking at the craftsmanship and guessing the size and weight of this column, I wondered about the process it must have gone through to become “rounded” out of a cubic block chunked from

the earth.

The encroaching forest had overgrown everything left behind when the quarry ceased operating, but I was easily able to find remnants. Giant wooden derrick masts still reach to the sky, supported by thick cable guy wires running like a spider web in every direction. A few deteriorating buildings still stand, vandalized and rotted beyond salvation.

Air compressors the size of automobiles remain, rusting away. The coal-fired steam boiler that once powered these compressors is now falling apart, but the compressors look like they could again provide the air needed to power jackhammers and stone drills. Tramway tracks still lead up the mountain to where they once ferried heavy granite blocks out of the pit and rolled them down into the stone-cutting sheds.

The answer to my question about converting a rectangular granite block into a circular column is revealed as I move through the ghost town. The answer is giant lathes, portions of which remain. The magnitude, horsepower and durability required of a lathe capable of rotating large chunks of granite at high speeds while chisels grind away at it is mind-boggling. The torque required to rotate tons of granite must have been enormous.

Whereas sawdust shavings spun off a woodworking lathe are generally harmless, the stone dust, chips and chunks of rock flying off this spinning granite would sandblast anyone nearby, and the noise must have been ear-piercing. Lifting tons of raw granite onto the lathe must have placed immense strain on the cables and wooden derricks. Lifting the finished column off the lathe must have been stressful, as a drop, break or crack in the column would mean starting all over.

Granite from this quarry was used in constructing many early railroad stations. Some, including the Laconia Passenger Station, remain standing today. Redstone granite was also used in buildings in Concord, Portland, Boston, New York, Washington, D.C., and as far away as Denver and Havana, Cuba. Grant’s Tomb in New York and the National Archives building in Washington, D. C., are among the many buildings containing granite quarried here.

Redstone felt the economic downturn of the Great Depression, but government contracts allowed production to continue, although on a reduced scale. World War II further interrupted the demand for granite. After the war, concrete began to replace granite as the preferred building material due to its lower cost and greater flexibility. By the early 1940s, much of the best quality rock at Redstone had played out and the outdated facility was no longer competitive.

2G8YBY8 Laconia Passenger Station is a historic railroad station with Richardsonian Romanesque style at Veterans Square in city of Laconia.

Records indicate 1948 was the last year granite was quarried from Redstone, and it was used to build a criminal court building in New York City. After completing the project, the quarry and entire Redstone village were sold. Residents living in company houses were given the first option to purchase their homes. Most of the valuable machinery was sold. The remaining equipment, rails, cables and outdated machinery that didn’t sell or that was too cumbersome to move for scrap was left where it lay.

The Nature Conservancy and state of New Hampshire now own the property, and it is managed by the Conway Conservation Commission. Hiking trails leading into the quarry have been developed that include some interpretive signs featuring old photos of the once-thriving quarry.

If you decide to hike up there and explore the site, keep an eye out for these interesting and informative signs. Probably wouldn’t hurt to keep an eye out for rattlesnakes, either.