A Town at the ‘Tipping Point’: As Mont Vernon Grows, Residents Fear Community Strain

Mont Vernon residents fear growth and rising home prices will strain community ties

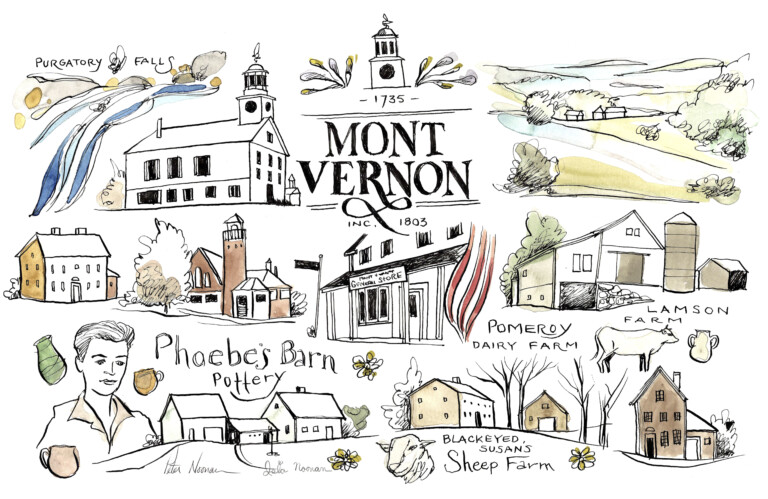

Blink and you’ll miss it,” people joke about driving through Mont Vernon. But you won’t miss what comes next. The road soon drops sharply, slicing through hay fields and woodland while hills rise in the distance. The panorama changes with the seasons. Verdant pastures give way to splashes of autumn color and winter’s icy treachery that has waylaid many a traveler.

The sign welcomes visitors to Mont Vernon as they travel north up Mont Vernon’s Grand Hill on Route 13.

While the view from Mont Vernon’s hill is one of the town’s most spectacular, there are other wonders to be found in this community of nearly 2,700 people tucked between Milford, Amherst, New Boston and Lyndeborough. Though small, Mont Vernon has an outsized hold on some of the area’s natural and cultural assets that draw people here, whether they come for a morning hike or stay a lifetime.

“It just has that quintessential New England feel to it — Main Street, the library, the McCollom Building and, of course, they are renovating the Town Hall now. It’s really picture-perfect,” says Dan Bellemore, who co-owns the Mont Vernon General Store, the town’s sole retail establishment.

Besides visitors from around the state and nation, tourists come from “all over the world,” including China, Japan and Europe. “We had the Brazilian bike team in here,” Bellemore adds, noting it’s a popular stopping point for motorcycle and bicycle groups traveling Route 13.

“They all come for the biking, the trails, Lamson Farm, just to get that country feel, and you can’t get that everywhere. It’s unique,” Bellemore adds. “Even in the winter, you can cross-country ski. You can walk through woods with snowshoes. That’s the appeal of Mont Vernon.”

The town has its own “Purgatorio” hidden deep in the woods. Hikers and seekers from far and wide make the descent to see Purgatory Falls plunge through the granite chasm. Legend has it the devil even visited it and left a molten impression of his footprint, still visible today.

The falls were a popular attraction during the height of the town’s resort hotel era in the late 1800s. How to get to Purgatory Falls remains one of the most commonly-asked questions at the general store, Bellemore says. The other is where can you buy gas. (You can’t. The town has no gas station.)

Mont Vernon has two family-run, working farms. The Pomeroys operate the town’s remaining dairy cow farm which, according to the New Hampshire dairy industry, is one of about 94 left in the state. And Julie Whitcomb and Matt Gelbwaks run Blackeyed Susan Sheep Dairy, the state’s first, and only, sheep dairy farm. The married couple previously operated Julie’s Happy Hens, a 3,000-bird chicken farm that they closed to transition to sheep in 2024.

“It hearkens back to the days gone by when you could go to the farm. People told us they came and bought eggs from us because this is what grandmother’s farm used to be like,” Gelbwaks says. And residents salute their agrarian past at Lamson Farm Day held each year at the former 310-acre dairy farm, which the town bought when it ceased operating in 1975.

Dan Bellemore, who co-owns the Mont Vernon General Store with Mike Wallenius, works with employee Dayna Towne. The store is in the center of Mont Vernon’s historic district and is the only retail establishment in town. It’s a popular stopping point for both locals and out-of-town visitors.

Arts also flourish here. Aspiring artists once studied at the village watercolor school operated by Phoebe Flory, who died in 2004. The barn now is a pottery school. The town is widely known for the annual “Messiah Sing!” held at the Mont Vernon Congregational Church. About 120 singers from as far away as Massachusetts and seven-piece professional orchestra perform Handel’s powerful oratorio.

“The effort … to bring that joyful noise at the beginning of the Christmas season is what we’re all about,” says publicity and staging manager Anne Dodd of the event that began in 1988. Many townspeople have sung in it at least once.

Eloise Carleton is among them. She moved here in 1962 after she married Alwyn Carleton, a son of one of Mont Vernon’s founding families. Mont Vernon was a quiet town of about 500 to 600 people when the couple settled at the crest of the hillside farm where Al Carleton’s parents raised dairy cattle and chickens. Amenities were few, but people were friendly and always pulled together when something needed to be done, she says. The sense of community and raw natural beauty are what she loved most.

While Al was a skilled hunter and outdoorsman, Eloise never fired a gun until one day early in their marriage. She sat in the car reading a book while Al “was shooting those stupid rats running around the Mont Vernon dump,” she recalls. Curious, she asked if she could try. He taught her to shoot and she was hooked. Al, who died in 2019, and Eloise became certified hunter safety training instructors and hunted in the surrounding woods with family and friends for decades.

Mont Vernon has changed a lot in recent years, Eloise says. It’s bigger, busier and is much more of a “bedroom town.” What does she miss most about the way it used to be?

“The wildness,” she says.

“I loved the trees and the close proximity to the woods,” adds Eloise, who moved to Milford two years ago, but still calls Mont Vernon home and visits often. “Those of us who like it a little bit wilder don’t like it quite as well (now). We love the animals coming into our yard — the bear, the moose and the deer.”

Then there was what Eloise calls that “one awful day” in 2009 when Kimberly Cates was murdered and her daughter maimed during a home invasion. Residents were stunned by the brutality of the random attack, which shattered any sense that living in Mont Vernon could shield them from that level of violence. “It was not something you would expect in a small town. It was heinous,” she says.

The year the Carletons married was a turning point for Mont Vernon, whose history has been a series of boons and busts since it broke away from Amherst and incorporated as a separate town in 1803. The town’s population hit a high point of 763 residents in 1830, then steadily declined to about 300 people in the 1920s-1930s, U.S. Census figures show. The town rallied from prior downturns largely by tapping in to advances in transportation and technology. It was on the cusp of another comeback.

A view of the western side of Route 13 unfolds before travelers leaving the hilltop village of Mont Vernon.

The rise of the automobile after World War II coupled with major defense contractor Sanders Associates locating in Nashua became a boon for Mont Vernon and surrounding towns. Sanders was hiring engineers in the 1960s, and many settled in the town’s vacant farms and homes. They included Darold and Sarah Rorabacher,

Bob and Eileen Naber, and Al Ryder.

“For a small town, that was a big influx of people,” says Eileen Naber, adding they were warmly welcomed when they came in 1962.

“We just felt so embraced,” she says. There were sledding parties, softball games, dinner parties, church groups, 4-H clubs and other activities, she says.

The Rorabachers settled in the former South Schoolhouse on Old Milford Road. Their daughter, Anna Rorabacher Szok, remembers the town was so small that residents came to their house to conduct town business with her mother, who was town clerk and tax collector. Her father was a selectman. Anna bought the house in 2011, and “(I) love it more than I ever did as a kid.

“I love (Mont Vernon’s) topography, the woods. I love the views. I love being in a rural place where Boston is still pretty close,” says Rorabacher Szok, who is president of the Mont Vernon Historical Society.

After more than a century of decline, the population surpassed its 1830 high point with 906 residents in 1970, the U.S. Census shows. By 1980, 1,444 people were living here.

“There are more people now, but less of them know each other,” Naber says. Community groups and activities either have fallen away or been subsumed by government, she says. And the demographics have changed.

“We’ve gone to an upscale residential community. All the old houses are still here, but all the new ones are big and fancy and very expensive,” she adds.

“What’s happening in Mont Vernon right now is if you don’t make a lot of money, you can’t afford to live in Mont Vernon,” Rorabacher Szok says, noting some of the new houses are selling “for almost a million dollars.” Median family income in 2023 was $171,429, and per capital income was $63,344, the state Economic & Labor Market Information Bureau reports.

Some of those interviewed say this growth and the changes it brings strain the fibers that keep community life strong. While the town still hosts its annual Spring Gala and holiday tree lighting, they say fewer things bring townspeople together on a regular basis. Even the weekly trip to the dump is going by the wayside as more people pay for private trash pickup.

Increasingly, more people don’t know each other, and it becomes easier to say unkind things about someone when you won’t face them in person, says Matt Gelbwaks. This partly explains the “vitriol” and “just plain old mean” things being posted on Facebook at a level unseen before, he adds.

Residents celebrated the addition of the Mont Vernon Town Hall to the National Register of Historic Places with the unveiling of a plaque at a brief ceremony on Aug. 24, 2024. The Town Hall is in the midst of rehabilitation and renovations. It is the second local site to be listed on the National Register; the other is Lamson Farm.

“The library certainly was a lightning rod for this,” he says. While the town has faced divisive issues before, plans to build a new $5.99 million library — $1.99 million of which is to be raised from taxes — plus a $683,600 access road flamed especially bitter divisions. The library article drew record voter turnout at the last two Town Meetings where it failed by 20 votes in 2023, but prevailed in 2024 by nine votes, the town clerk says. Groundbreaking occurred in September. The library should open in fall 2025.

Eloise Carleton says the librarians have made the existing library “a real community center” where children, teens and senior citizens can gather. “I think the divisiveness will heal and people will be happy with what they’ve got.”

Others say they hope the town can heal from the rancor and factions can coexist again.

“What I think is still special is that we are a small, intimate town that has a fair degree of pride over who we are and what we’ve been…There is no reason why we should not celebrate the fact that we are an archetypical New England town,” Gelbwaks says. He sees the town at a “tipping point” if the harm is not healed.

“If they are not corrected, we lost everything that is special in the town. We just become another town.”